Scientists studying Renaissance-era artworks and documents say they have recovered tiny traces of DNA from artefacts associated with Leonardo da Vinci, reopening questions about one of history’s most scrutinised figures through an unexpected scientific lens. Da Vinci (1452–1519) embodied the ideal of the Renaissance man, a painter of Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, but also an anatomist, engineer and relentless observer whose notebooks blurred the boundary between art and science centuries before modern disciplines existed. The work forms part of a growing scientific approach known as arteomics, which examines biological traces left on historical objects to better understand their origins, handling and environments, and was recently published as a preprint on bioRxiv, meaning it has not yet been peer-reviewed.

Artefacts, ancestry and genetic clues

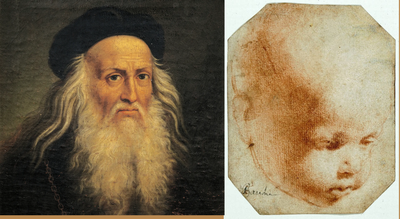

Researchers recovered trace DNA from a red chalk drawing on paper known as Holy Child, which is possibly by da Vinci, as well as from letters written by Leonardo’s grandfather’s cousin, Frosino di Ser Giovanni da Vinci, held in a historical archive in Italy. They also analysed a letter penned by one of Leonardo’s cousins. In April 2024, microbial geneticist Norberto Gonzalez-Juarbe carefully swabbed the Holy Child drawing in a private New York collection using COVID-19-style test swabs. The red chalk sketch, attributed to da Vinci’s circle but of disputed authorship, features the characteristic left-handed hatching and sfumato technique associated with Leonardo da Vinci.

Image of Leonardo da Vinci’s ‘Holy Child’, from the book ‘Leonardo’s Holy Child’ by Fred R. Kline.

Some Y-chromosome DNA sequences found on the Holy Child artwork and in the cousin’s letter appear to belong to a genetic grouping associated with shared ancestry in Tuscany, where da Vinci was born. When compared against large Y-chromosome reference databases, the closest match fell within the broad E1b1 / E1b1b lineage, which is found today at notable frequencies in southern Europe, including Italy, North Africa and parts of the Near East. According to Science magazine, the team recovered abundant human DNA, especially from the back of the drawing, along with DNA from sweet orange trees cultivated in Medici gardens during the Renaissance, an environmental fingerprint that researchers suggest may point to the work’s historical context and possible authenticity. Some of the DNA may be from da Vinci himself, Science magazine reported. However, researchers stress that this does not amount to conclusive proof.

Why proving identity is so difficult

Establishing whether any genetic material recovered from the artefacts belongs to Leonardo da Vinci is extremely complex. Scientists cannot verify the sequences against DNA known to have come from da Vinci himself because he has no known direct descendants. His burial site was also disturbed in the early 19th century, and his remains were reportedly scattered during the French Revolution, further complicating any attempt to recover confirmed genetic material. “Establishing unequivocal identity … is extremely complex,” said David Caramelli, an anthropologist and ancient DNA specialist at the University of Florence, who works with the Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project, speaking to Science. Because the team was explicitly searching for male-line DNA and focusing on Y-chromosome markers, the DNA collection was carried out exclusively by female scientists to reduce the risk of contamination.

A minimally invasive method

Historical artefacts can accumulate DNA from their environments and from the people who created, handled or conserved them over centuries. Studying such objects without damaging or contaminating them has long posed a challenge. To address this, scientists developed what they describe as a “minimally invasive” method to recover what they call “biological signatures of history” from Renaissance artwork and correspondence linked to da Vinci’s family. Researchers used a gentle swabbing technique similar to those already used in museums, collecting flakes of skin, sweat residue, microbes, plant pollen, fibres and environmental dust from the artefacts.

Forensic biologist Rhonda Roby (center) swabs Holy Child, a 16th century red chalk sketch perhaps created by Leonardo da Vinci, for DNA in April 2024. (Marguerite Mangin) via ancient-origins.net

From these materials, they extracted tiny amounts of DNA. Most of it came from bacteria, fungi, plants and viruses, providing insight into the artefacts’ materials, storage environments, conservation treatments and handling over time. A smaller portion came from humans. “We recovered heterogeneous mixtures of non-human DNA,” the researchers wrote in a study posted to arXiv, “and, in a subset of samples, sparse male-specific human DNA signals.”

Environmental and historical signals

The non-human DNA offered additional historical clues. Researchers said certain plant traces could help situate artefacts geographically and culturally. “Certain non-human DNA may help us to understand the artefact composition, possible materials used, and the environment and geology of the pieces obtained during the Renaissance in Florence and other areas of Europe,” they wrote. They cited Italian ryegrass as one example, noting it could indicate that an artefact originated in Italy during the 1400s or 1500s. They also pointed to riparian species such as Salix (willow), explaining that these plants were abundant along the Arno river and commonly used for basketry, bindings, scaffolding and charcoal production in artisanal workshops. “The unique presence of Citrus spp in the ‘Holy Child’ may provide a direct link to historical context,” the scientists said, while emphasising that plant DNA can come from multiple sources, including dust, conservation work and later handling.

Comparisons, controls and limits

The Holy Child drawing was one of many objects analysed. Researchers also examined letters written by Leonardo’s cousin, drawings by other artists, including Filippino Lippi, Andrea Sacchi and Charles Flipart, as non-Leonardo comparisons, as well as frames, environmental surfaces from collection rooms in Italy and the United States, commercially acquired artworks from the same period, and cheek swabs from modern humans. The Y-chromosome markers identified in the drawing were compatible with paternal-line patterns found in other Leonardo-associated objects. However, the samples also contained DNA from a wide variety of people who may have handled the artefacts over centuries, including modern handlers. “To enable stronger claims, especially relating to provenance, geolocation, or historical characteristics, future work is needed to help distinguish artefact-associated signal from modern handling,” the researchers cautioned. Go to Source