Long before Silicon Valley discovered the word “Bengaluru” and well before Indian-origin CEOs became a familiar sight on Fortune 500 earnings calls, American newspapers had already been introduced to a particular kind of Indian engineer. He was impossibly smart, socially earnest, slightly baffled by corporate life, and educated at an institution most Americans could not locate on a map. His name was Asok, and he lived in the cubicle universe of Dilbert.For millions of American readers, this was their first sustained encounter with the Indian IITian as a cultural archetype.

Who was Asok?

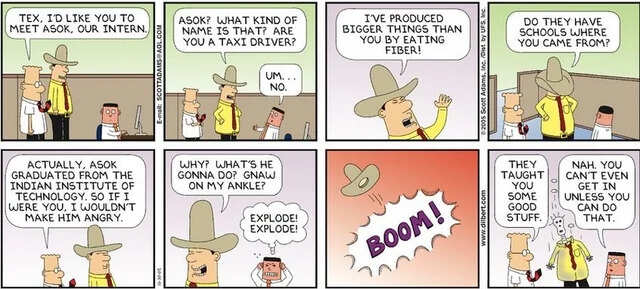

Asok was introduced in the mid-1990s as a young intern from India, explicitly described as a graduate of the Indian Institutes of Technology. Within the logic of the strip, this single credential explained everything else. Asok routinely outperformed senior engineers, solved complex technical problems instantly, and displayed a level of raw intellect that bordered on the absurd.Yet he was not portrayed as a swaggering genius. Instead, Asok was polite, literal-minded, and often confused by the irrational rituals of American corporate life. His brilliance did not grant him power. It merely made the stupidity around him more visible. That tension became the joke.

Why Dilbert mattered

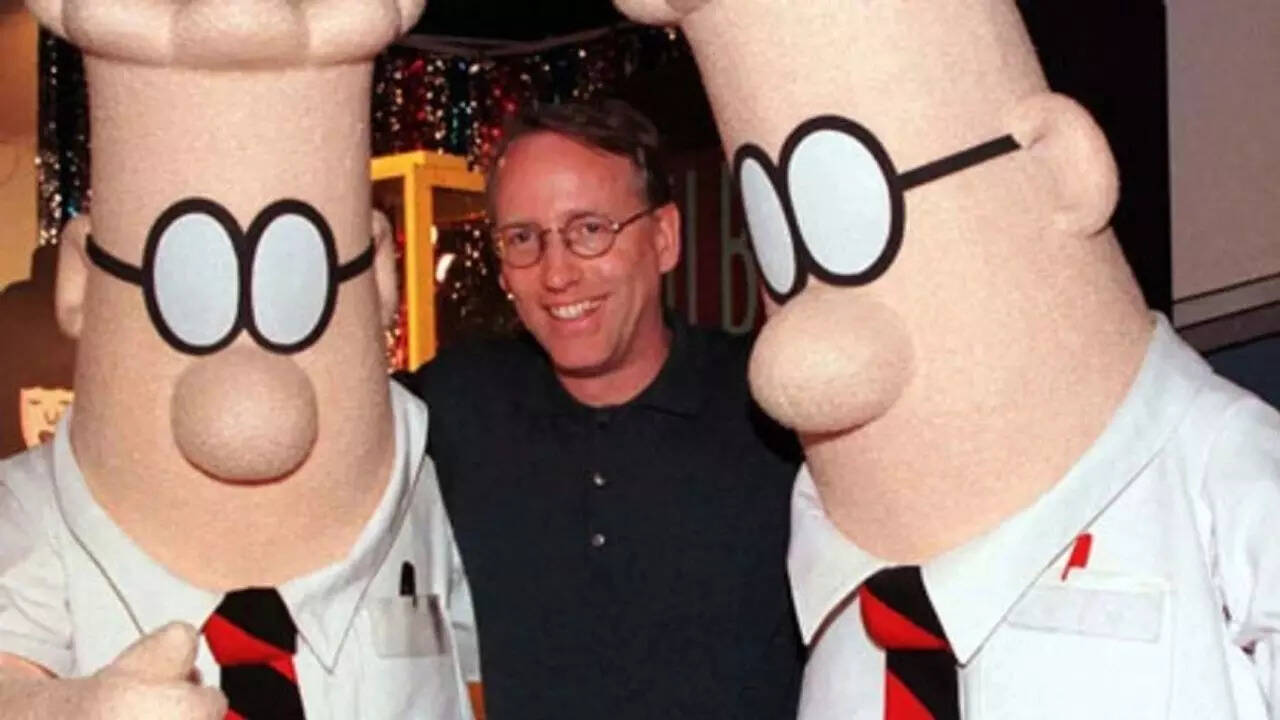

Created by Scott Adams, Dilbert functioned as a daily anthropology of white-collar America. Managers were clueless. Strategy was meaningless. Meetings existed to justify themselves. Engineers were the only adults in the room.As the US tech industry globalised through the 1990s, the strip absorbed that reality. Offshore teams, outsourcing anxieties, and immigrant engineers began to appear. Asok was not an exotic addition. He was treated as a logical outcome of a system that increasingly depended on technical skill it could neither fully understand nor properly reward.In that sense, Dilbert did not explain globalisation. It normalised it.

The IITian as cultural shorthand

What Dilbert did quietly, but effectively, was turn “IIT” into a cultural signal. The strip never paused to explain entrance exams, rankings, or academic prestige. It did not need to. Asok’s competence did the work.Over time, American readers learned to associate IIT with extreme intelligence in the same way they associated management with incompetence. The Indian engineer was not comic because he was foreign. He was comic because he was correct in a system built to ignore correctness.This was an important distinction. Asok was not the butt of the joke. The organisation was.

Outsider brilliance, insider blindness

Asok’s repeated failure to advance within the company reflected a deeper truth about corporate culture. Technical excellence did not translate into authority. Social signalling mattered more than substance. Knowing the answer was less valuable than knowing how to present it badly in a meeting.By placing an IIT-trained engineer inside this ecosystem, Dilbert sharpened its satire. Asok’s presence made the irrationality of corporate America impossible to miss. The smarter he was, the dumber the system appeared.For Indian readers, especially aspiring engineers, Asok became a strange point of identification. He was proof that excellence travelled. He was also a warning that excellence alone was not enough.

Cultural impact beyond the comic strip

Dilbert was syndicated widely, read daily, and absorbed casually. That mattered. It meant that the idea of an Indian engineer from IIT entered American consciousness not through immigration debates or business journalism, but through humour.By the time real-world IIT graduates began occupying senior roles in US tech firms, the archetype was already familiar. The comic strip had done the cultural pre-work. It had made the Indian IITian legible.Not glamorous. Not heroic. But unquestionably competent.

The bigger picture

Asok did not single-handedly shape America’s view of Indian engineers. But he arrived early, stayed long, and reached far. In doing so, Dilbert helped introduce a figure that would soon become central to the global technology story.The Indian IITian did not first appear in America as a CEO. He appeared as an intern in a cubicle, quietly solving impossible problems while the adults argued in meetings.That, in retrospect, was remarkably accurate. Go to Source