On a crisp winter morning, when the sun struggles to cut through a grey, smoky haze, many of us glance at the air-quality index like a daily horoscope, the number that decides whether we mask up, skip a walk, or brace for another day of breathing toxic air. But what do those figures actually mean for our lungs? Why does 200 feel unbearable while 500 feels apocalyptic? And as smoke from stubble burning mixes with vehicular and industrial pollution, what is all that particulate matter really doing inside the body?Here is a look at the mechanics of the AQI, and what a pulmonologist wants you to know before the next toxic plume rolls in.

Why AQI isn’t just a number: Decoding what it measures

For years, India’s air-quality data was buried in technical charts and numbers, leaving most people unsure of what the readings meant for the air they breathed. Without a clear, accessible system, public engagement with pollution remained limited.To change this, the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) set out to create a national Air Quality Index (AQI) that could translate complicated measurements into simple, accessible categories. An expert group, bringing together doctors, air-quality scientists, academics, NGOs, state pollution boards, and technical inputs from IIT Kanpur, developed what eventually became India’s AQI. A draft was released in October 2014 for public and institutional feedback, and after detailed review, the national framework was finalised.The AQI is designed to tell people, at a glance, not just how polluted the air is, but what that level of pollution could mean for their health. It classifies air quality into six categories: Good, Satisfactory, Moderately Polluted, Poor, Very Poor, and Severe. The index accounts for eight major pollutants with 24-hour standards and calculates individual sub-indices for each as long as there is data for at least three pollutants, one of them necessarily PM2.5 or PM10, an AQI can be computed. The highest (or “worst”) sub-index becomes the overall AQI number for that location.The AQI measures key pollutants such as PM2.5, PM10, ozone, carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen dioxide. Among them, PM2.5 is considered the most harmful because its tiny particles can travel deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream, leading to serious health risks. The World Health Organisation (WHO) advises keeping PM2.5 levels below 5 micrograms per cubic metre (µg/m³) annually, and under 15 µg/m³ for 24 hours.

Why a 500 in India isn’t a 500 in the US

The US AQI, like India’s, runs on a 0–500 scale, but with one key difference. Its highest category, “hazardous,” begins at 301 with no upper cap, so readings can go well beyond 500. The two countries also use different formulas to calculate their scores, which means the same pollution data can produce different AQI values. In short, the Indian and US scales don’t line up exactly and can’t be directly compared.

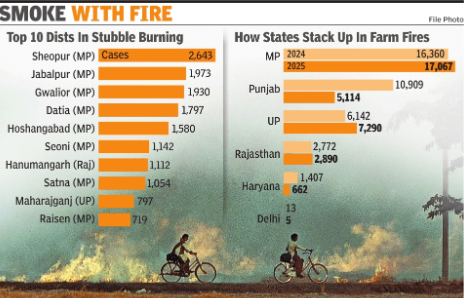

How stubble fires feed the winter smog

Every winter, vast stretches of northern India, from Punjab and Haryana to neighbouring states, witness the burning of leftover crop stubble as farmers clear their fields for the next sowing season. This practice, known as crop residue burning (CRB), remains a persistent environmental challenge in India and many agricultural regions around the world.CRB is a major driver of fine particulate pollution, especially PM2.5, that engulfs Delhi and the wider NCR region each winter. These microscopic particles pose a heightened health threat, not only to residents but also to farmers living in and around the burn sites. Because PM2.5 particles are small enough to penetrate deep into the respiratory system, they can lodge along the delicate lining of the alveoli in the lungs.

.

A growing body of scientific evidence links PM2.5 exposure to significant health risks. Short-term exposure can impair lung function and worsen conditions like asthma and heart disease. Over the long term, the dangers intensify; prolonged inhalation has been associated with chronic bronchitis, reduced lung capacity, and increased mortality linked to lung cancer and cardiovascular illnesses.

Eleven cities, zero clean air days: Delhi remains the worst of them all

Delhi has once again topped the charts as India’s most polluted city, according to a decade-long AQI assessment by Climate Trends covering 2015 to November 2025. The analysis shows that no major Indian city has reached safe air-quality levels at any point in the past ten years, underscoring the severity of the national pollution crisis.

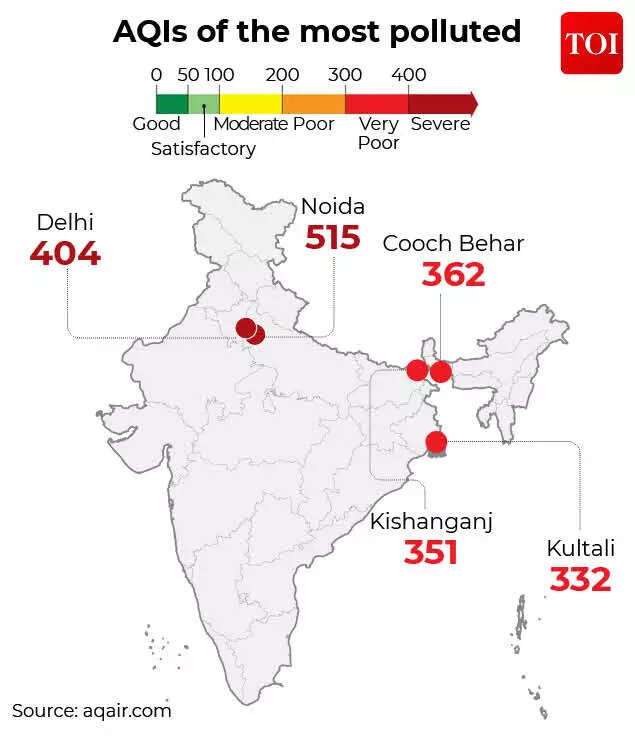

aqi

Delhi remains the worst-hit, followed by Noida, which recorded an alarming AQI of 515. Other heavily polluted regions include Cooch Behar (362), Kishanganj (351), and Kultali (332), reflecting how toxic air has spread far beyond the metros and deep into smaller districts. The data points to a nationwide public-health emergency, with the capital continuing to sit at the centre of India’s pollution burden.

‘Acute respiratory distress’: How AQI 200 vs 500 hits your body

Dr Kuldeep Kumar Grover, head of critical care and pulmonology at CK Birla Hospital in Gurugram, says the body reacts almost immediately when pollution levels rise. Fine particles irritate and inflame the airways, leading to coughing, excess mucus, and reduced lung function, while the heart and blood vessels come under added strain due to oxidative stress, constricted vessels, and a heightened tendency for clotting.”The cardiovascular system also responds to pollution by inducing oxidative stress, blood vessel constriction, and an increased tendency toward blood clotting.”

Citizens protest against pollution in Mumbai (PTI)

At an AQI of around 200, the body experiences noticeable but manageable stress; symptoms like throat irritation, headaches, and breathlessness are common, especially for vulnerable groups. But when levels reach 500, the exposure becomes overwhelming. Inflammation intensifies, asthma can worsen quickly, blood pressure may rise, and even healthy people may struggle with oxygen exchange. Sustained exposure at this severity can lead to acute respiratory or cardiac complications, Dr Grover adds.

PM2.5: The microscopic pollutant with massive health consequences

Surface pollution from stubble burning and urban sources exposes people to PM2.5, PM10 and carbon monoxide, the dominant winter pollutants. The tiniest of these, PM2.5, can slip past the body’s natural defences, lodge deep in the lungs, and even enter the bloodstream. Carrying toxic metals and reactive chemicals, these particles spark chronic inflammation and gradual tissue damage. Over time, doctors see faster loss of lung function, recurring bronchitis, worsening asthma, and higher risks of heart and vascular disease.”Long-term exposure also increases risks of lung cancer, preterm birth, and impaired cognitive development in children. The cumulative effect of this pollution is almost akin to the long-term effects of smoking in some highly polluted regions,” Dr Grover said.

When pollution surges, who’s most vulnerable?

Children, pregnant women, and older adults face greater risks as AQI levels climb because their bodies are more vulnerable to pollution-induced stress. Children breathe faster and have developing lungs, making AQI levels above 150 likely to trigger coughing, wheezing, and fatigue.Pregnant women, who already have reduced oxygen reserves, may experience breathlessness when pollution rises above 200, and prolonged exposure has been linked to complications such as “low birth weight and preterm labour.” Older adults, especially those with heart or lung conditions, can develop chest tightness, irregular heartbeat, or worsening COPD even at AQI 150–200, said Dr Grover.

India Gate covered in a layer of smog (ANI)

On the other hand, for people with asthma or chronic bronchitis, polluted air intensifies existing inflammation. Irritants like PM2.5 and ozone narrow the airways, increase mucus, and heighten sensitivity to triggers, leading to more frequent wheezing, coughing, breathlessness, and greater reliance on rescue inhalers. High pollution days also increase the risk of asthma attacks, respiratory infections, and a faster decline in lung function.”Patients should follow their treatment plans closely, avoid outdoor activity at times of peak pollution, and use preventive medication as recommended by their clinician,” Dr Grover said.

How to shield yourself on the worst days

On days when air quality plunges into the “very poor” or “severe” range, the most important strategy is reducing total exposure, said Dr Grover.Indoors, keeping windows shut, avoiding smoke or incense, and using a certified HEPA purifier can significantly lower pollutant levels. Outside, it’s best to limit activity, especially exercise, which draws particles deeper into the lungs. Only well-fitted N95 or FFP2 masks offer real protection; cloth and surgical masks do little to block PM2.5. Supporting measures like staying hydrated, using nasal saline rinses, and closely monitoring symptoms help reduce irritation. People with chronic lung or heart conditions should keep medications handy and follow their action plans carefully. Avoiding peak pollution hours, typically early mornings and evenings, remains one of the simplest ways to cut exposure.As winter smog thickens and AQI levels swing from unhealthy to severe, the message from experts is clear: pollution is not just an environmental issue but a direct, measurable threat to health.From choosing the right mask to avoiding peak smog hours and protecting vulnerable groups, even small, consistent steps can significantly cut exposure. And while individual action offers only partial defence, experts say awareness is the first line of protection until long-term, systemic solutions begin to clear the air for good. Go to Source