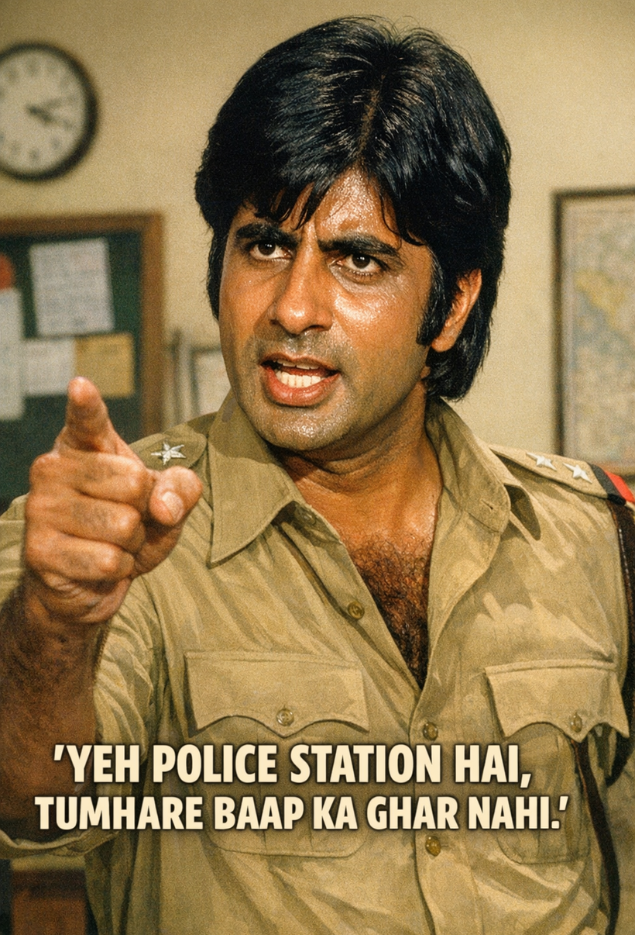

Ye naya Hindustan hai…History might disagree, at least in the cinematic verse. Everything repeats, and the return of angry young men on screen is one such phenomena. And so is the hyper nationalistic movies. ‘Yeh police station hai, tumhare baap ka ghar nahi’

Half a century ago, that line from Zanjeer didn’t just earn applause — it gave voice to a generation’s anger. Today, that anger is back in Indian cinema, louder, bloodier and far more profitable. With Dhurandhar storming the box office and rewriting records week after week, the return of the angry young man is no longer a creative coincidence. It is a cultural moment. But this time, the anger isn’t quite pointing in the same direction.Released on December 5, Dhurandhar has only begun to slow down in its fifth week after a month-long, record-breaking run. The Ranveer Singh-led film, featuring Arjun Rampal, R Madhavan, Sanjay Dutt and Akshaye Khanna, has crossed the lifetime collections of Stree 2, Jawan and Pushpa 2. It has stayed remarkably strong despite competition from Hollywood spectacle Avatar: Fire And Ash and Hindi releases such as Tu Meri Main Tera and Ikkis. Its success is not just about scale or star power — it signals how deeply the angry male protagonist has re-entered the mainstream imagination. From here, Indian cinema’s relationship with anger, power and masculinity tells a story that is as political as it is cinematic.

Why was the 70s young man angry?

The template was set in the 1970s against the backdrop of Emergency. In Zanjeer, Amitabh Bachchan’s Vijay Khanna tells the system exactly where it stands. In Deewar, when asked to choose between law and loyalty, he delivers one of Hindi cinema’s most enduring lines: “Mere paas maa hai.” It wasn’t bravado. It was a moral position.The angry young man of that era was shaped by a country struggling with inflation, unemployment, labour unrest and widespread corruption. Films like Deewar (1975), Kaala Patthar (1979) and Kaalia (1981) were steeped in a sense of betrayal. The state had promised dignity and justice; instead, it delivered scarcity and indifference.These protagonists were anti-establishment by design. They didn’t trust institutions because institutions had failed them. When Bachchan growled, “Aaj khush toh bahut hoge tum,” it was a class confrontation. Film scholars often describe this phase using Antonio Gramsci’s idea of counter-hegemony: cinema became a site where the working class could symbolically push back against dominant power structures.Violence existed, but it was rarely celebratory. The angry young man was tragic, burdened by his choices, aware that justice came at a cost.

The new angry men arrive

Fast forward to the last decade, and the angry man is back—bigger, louder and more commercially potent than ever. Films like KGF., Kabir Singh, Pushpa: The Rise and Animal have drawn massive audiences across languages.But listen closely to what these men are angry about.In Kabir Singh, the protagonist declares, “Jo mera nahi ho sakta, woh kisi aur ka bhi nahi ho sakta.” His rage isn’t directed at a broken system but at a woman who refuses to conform. In Animal, Ranbir Kapoor’s character boasts, “Papa ke liye main kuch bhi kar sakta hoon,” as familial obsession morphs into unchecked violence. The films don’t question these impulses—they aestheticise them.

Even in Pushpa, when Allu Arjun swaggers through the forest declaring, “Pushpa naam sunke flower samjhe kya? Fire hai main,” the line captures the shift. Pushpa doesn’t dismantle corruption; he perfects it. His rebellion is not against power, but against exclusion from power.Similarly, KGF’s Rocky doesn’t dream of reform. He dreams of domination. His worldview is summed up in the idea that power must be seized and held at any cost, not questioned or redistributed.

From fighting corruption to becoming it

This is the crucial difference between the angry men of the 1970s and today. Earlier heroes fought corrupt systems because those systems denied dignity. Today’s heroes often aspire to control the system itself.Film theory helps explain this turn. Where earlier cinema channelled collective anger, contemporary films reflect a more individualistic worldview. Neoliberal masculinity—where success is personal, dominance is virtue, and empathy is weakness—has found a powerful visual language in popular cinema.The audience response is telling. Viewers cheer not because the hero questions authority, but because he exercises it without restraint. Anger has shifted from resistance to entitlement.

When state tells you what to watch

Running parallel to this trend is the rise of overtly pro-state films. Titles such as Uri, Article 370, The Sabarmati Report, The Kerala Story and The Vaccine War have framed the state as decisive, morally upright and beyond scrutiny.In Uri, the line “How’s the josh?” became a national catchphrase—not of protest, but of affirmation. The cinema of anger, once suspicious of power, now often works in sync with it.Political communication scholars note that popular culture doesn’t merely mirror public sentiment—it helps shape it. When rage is directed outward at designated enemies rather than upward at systems of power, it reinforces the status quo rather than challenging it.

How comfortable is the film fraternity?

Since Dhurandhar divided people over whether to appreciate the filmmaking of it or criticise the propaganda of it, Hindi film industry actor Hrithik Roshan put it the right way: “I may disagree with the politics of it, and argue about the responsibilities us filmmakers should bear as citizens of the world. Nevertheless, can’t ignore how I loved and learnt from this one as a student of cinema. Amazing.”Andhadhun actor Radhika Apte too, recently expressed concern over the rise in violence in Indian cinema.”I’m deeply disturbed by the violence at the moment that is selling as entertainment,” said Apte in an interview with the Hollywood reporter. She did not shy away from calling out violence against women in films.”I find it disturbing that actresses are doing films that demean women,” she said, calling for collective responsibility. “I think we need to collectively stop doing them. They might be throwing money at you, but you’re rich already. We need to stop because this is very harmful.”

What’s really changed

The angry men are back. They dominate box office charts, shape popular culture and command extraordinary influence. But unlike their predecessors, they no longer ask uncomfortable questions of power.The angry young man of the 1970s emerged from social fracture and spoke to collective injustice. Today’s angry man thrives on certainty—certain of his right to control, to punish, to dominate. His rage does not unsettle the system; it often reinforces it.

As Dhurandhar continues its theatrical run, it prompts a larger question for Indian cinema: Is this a revival of rebellion, or has authority simply been repackaged in the language of anger?Well, Naseeruddin Shah’s character in A Wednesday puts it right: Sawaal poochhne ka waqt kab ka nikal chuka hai. Go to Source