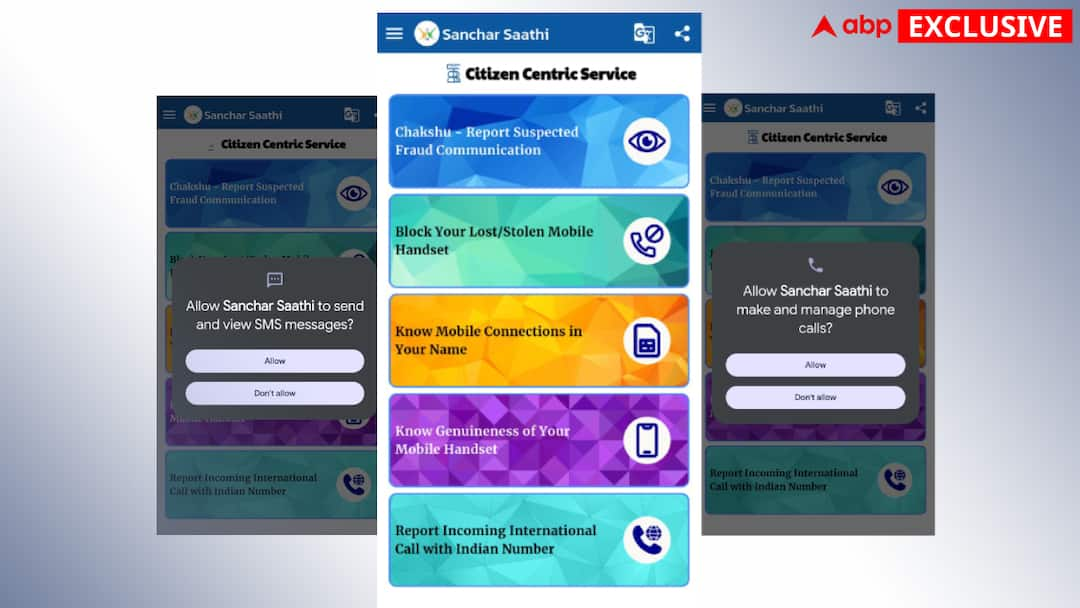

Sanchar Saathi:The Centre’s directive requiring all smartphone manufacturers to pre-install the Sanchar Saathi app has ignited a fierce legal and public debate, with digital rights advocates calling the move a step toward state-controlled digital infrastructure and the government insisting the measure protects citizens from cyber fraud.

Under a recent Department of Telecommunications (DoT) order, phone makers must ensure the app is visible, functional and cannot be disabled when a user first sets up a new device. Existing devices may also receive the app through software updates. Union Communications Minister Jyotiraditya Scindia has repeatedly stated that the app is both optional and deletable, and has denied any surveillance intent.

However, legal experts remain unconvinced.

‘Mandatory-Voluntary Toggle Raises Red Flags’

Speaking to ABP Live, senior technology lawyer and online civil liberties advocate Mishi Choudhary sharply criticised the government’s approach.

“This is yet another example of using ‘Directives’ to take away user autonomy, make a mockery of consent and have 24 hours State in My Home measure,” she said.

She argued that toggling between claims of mandatory and optional use mirrors what she describes as a familiar pattern. “The government keeps toggling between mandatory-voluntary as it builds facts on the ground, just like we saw with Aadhaar,” she said, adding that requiring manufacturers to preload a state-developed app amounts to coercion even if users are later allowed to delete it.

Privacy, Constitutionality And The Puttaswamy Test

Choudhary also questioned the constitutional validity of the move, pointing to the landmark 2017 Supreme Court ruling that established privacy as a fundamental right.

“This is legal untenable and fails the Puttaswamy test. Under the constitutional standard any interference with privacy or device autonomy ideally should have clear legislative basis and meet the necessary and proportionality test,” she said.

For those unaware, the Puttaswamy test decides whether state actions affecting privacy are constitutional. It requires three conditions: a legal basis for the action, proof that the measure serves a legitimate public interest, and proportionality, meaning the action must be narrowly tailored and not excessive compared to its intended purpose.

She added that statements of intent are not legal safeguards, noting, “Statements of intent are not a safeguard against surveillance. Citizens should never rely on, ‘Trust me dude assurances’ of politicians who aren’t experts.”

Cybersecurity Experts Say App Solves Only Part Of The Problem

The government argues the app helps reduce phone-based fraud by flagging tampered IMEI numbers, blacklisted phones, and fraudulent mobile connections. Over 1.75 crore fake SIMs and lakhs of stolen phones have reportedly been identified through Sanchar Saathi so far.

But cybersecurity professionals say the app addresses only early-stage fraud and may not meaningfully prevent sophisticated attacks.

Choudhary echoed this point strongly. “Sanchaar Saathi purports to solve a problem by addressing the wrong issue. What we have seen from global experience is that the major fraud vectors today are social engineering, like phishing, smishing, remote access apps, SIM swap, mule bank account, fake loan apps, cross-border call centres. These require financial network controls, not a phone side app,” she said.

‘Function Creep’ Concerns Grow

Privacy advocates warn that embedding a state-owned system directly into personal devices risks what they call “function creep”, the expansion of its capabilities over time without public scrutiny or legislative oversight.

“This is the start of a slippery slope of function creep. Such deep integration of state software on private devices ensures an expansion of surveillance capacities without fresh public debate each time new changes are made,” Choudhary said.

She also questioned the principle behind the mandate, saying, “Government has no business being in our devices that are more intimate to us than our loved ones.”

A Critical Question

With political opposition mounting, industry players seeking clarity, and government ministries signalling they may “re-examine” the mandate, the coming weeks may determine whether Sanchar Saathi becomes another Aadhaar-style nationwide infrastructure, or a policy that is rolled back under public pressure. At the time of writing, the Centre removed the mandatory pre-installation of Sanchar Saathi app on mobile phones for manufacturers.

For now, the dispute sits at the intersection of cybersecurity, constitutional law, and digital governance, posing a critical question for the world’s second-largest smartphone market: Where should the line be drawn between public safety and personal digital autonomy?