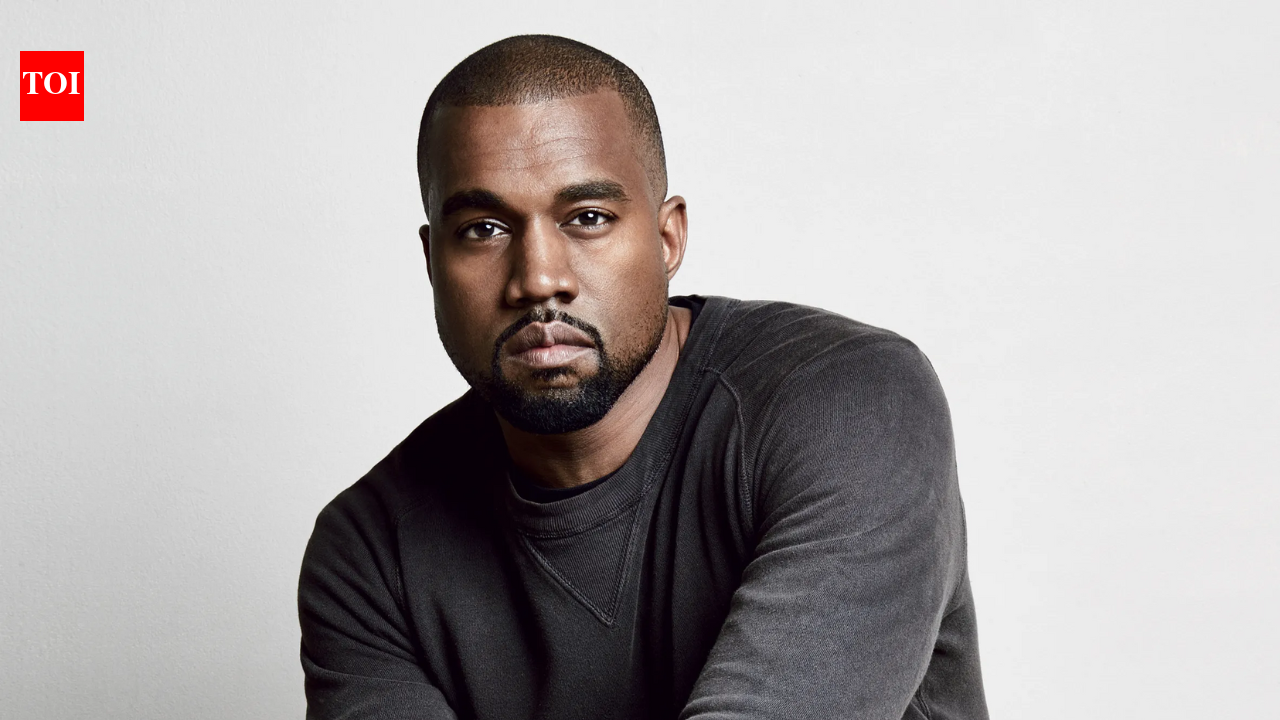

When US rapper Kanye West, also known as Ye, published a full-page apology for antisemitic behaviour in The Wall Street Journal, he appeared to be seeking closure after years of controversy. Instead, a single line in the letter reignited a different and older debate, prompting Hindu groups to accuse him of perpetuating a historical misunderstanding that has long stigmatised a sacred religious symbol.

What Kanye West said

In the paid advertisement titled “To Those I’ve Hurt”, Ye apologised for a series of antisemitic remarks, public statements and actions that had led to widespread condemnation and the collapse of several business partnerships.He attributed his behaviour to an undiagnosed frontal-lobe brain injury from a 2002 car accident and to bipolar disorder, describing how prolonged manic episodes caused him to lose touch with reality and exercise poor judgment. Reflecting on his use of Nazi imagery, Ye wrote that in a fractured mental state he “gravitated toward the most destructive symbol I could find, the swastika,” and acknowledged selling T-shirts bearing the symbol. While the letter explicitly stated that he is “not a Nazi or an antisemite” and expressed love for Jewish people, it made no distinction between the Nazi emblem and the ancient religious symbol known as the swastika. That omission became the focal point of the backlash.

What the Coalition of Hindus of North America said

The Coalition of Hindus of North America (CoHNA) condemned Ye’s wording, calling it “deeply insulting” to Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and other Dharmic communities.The organisation said Ye’s apology repeated a basic historical error: Adolf Hitler did not describe the Nazi symbol as a swastika. The Nazi Party referred to it as the Hakenkreuz, or “hooked cross”. According to CoHNA, equating the two symbols collapses vastly different historical and civilisational contexts into a single narrative of hate.CoHNA also urged The Wall Street Journal to issue a clarification, arguing that publishing the apology without contextual correction allowed a long-debunked misconception to be amplified. While acknowledging Ye’s attempt to apologise for antisemitic harm, the group said accountability must not come at the cost of misrepresenting living religious traditions.

Why the swastika is repeatedly misunderstood

The confusion between the swastika and Nazi symbolism is largely the result of early 20th-century Western reporting. As Nazi Germany rose to power, English-language media frequently translated Hakenkreuz as “swastika” for convenience, even though the Nazis themselves did not use that term.Over time, repetition turned that mistranslation into convention. In Western public consciousness, the word “swastika” became almost exclusively associated with Nazism, eclipsing its far older presence across Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism, where it symbolises auspiciousness, continuity and well-being.Historians argue that this collapse of meaning distorts history in two directions. Nazi ideology is inaccurately described when its own terminology is ignored, while Dharmic traditions are harmed when their sacred symbols are reduced to shorthand for European fascism. Precision, they say, is essential not only for cultural sensitivity but for historical accuracy.

How Hindus have tried to reclaim the symbol

In recent years, Hindu, Buddhist and Jain groups have stepped up efforts to reclaim and contextualise the swastika through education campaigns, interfaith dialogue and legal advocacy. These initiatives aim to explain the difference between the Nazi Hakenkreuz and the religious swastika, particularly in schools, museums and public discourse.Some of these efforts have translated into legislative recognition in parts of North America, where lawmakers have formally acknowledged the distinction between the two symbols. Community leaders stress that reclaiming the swastika is not about downplaying Nazi atrocities, but about preventing an ancient religious emblem from being permanently defined by its 20th-century misuse.For practitioners, the issue is deeply personal. The swastika continues to be used in daily worship, festivals, weddings and rites of passage. Its mischaracterisation shapes public perception and, at times, exposes communities to suspicion or hostility.

Why this controversy matters

Ye’s apology illustrates how historical misunderstandings can persist even in moments intended to heal. For Hindu organisations, the issue is not the artist’s intent, but the ease with which a global public figure could repeat an error that scholars and communities have spent decades trying to correct.The episode underscores a broader lesson history offers repeatedly: when symbols are flattened and stripped of context, attempts to confront one injustice can end up creating another. As debates around hate, memory and accountability continue, Hindu groups argue that accuracy is not a technicality. It is the foundation of understanding. Go to Source