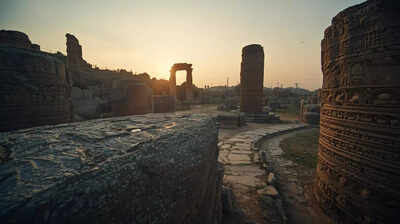

According to World Atlas, Göbekli Tepe sits on a low limestone ridge in southeastern Turkey, not far from the Syrian border, and continues to unsettle long-held ideas about early human societies. The site was first identified in the 1960s, but its significance only became clear decades later. Radiocarbon dating places its construction between about 9600 and 8200 BCE, far earlier than Stonehenge and long before farming was thought to be established. What remains visible today are rings of large T-shaped pillars carved from local stone, some standing more than five metres tall. Their scale and finish raise quiet but persistent questions about who built them, how they organised themselves, and what drew people to this place so early.

Göbekli Tepe was built thousands of years before civilisation was meant to begin

One of the most striking aspects of Göbekli Tepe is its age. It was built at a time when people in the region are believed to have lived as hunter-gatherers, moving seasonally and relying on wild resources. Agriculture, pottery, and permanent villages are thought to have come later. Yet the effort required to quarry, shape, transport, and erect the pillars suggests planning and cooperation over long periods. This does not sit comfortably with older models of small, loosely connected groups.

The pillars dominate the landscape and the debate

More than twenty structures have been identified so far, many arranged in circular or oval layouts. At the centre of several stands, two taller pillars facing one another, surrounded by smaller stones set into walls. Some pillars are estimated to weigh up to 50 tonnes. Their surfaces are carved with reliefs of animals such as foxes, snakes, scorpions, lions, and birds. A few show stylised human features, including arms and hands, giving them an almost bodily presence without fully becoming figures.

Special buildings suggest non-domestic use

Archaeologists working at the site have distinguished ordinary buildings and what they call special buildings. The latter contain the largest and most elaborate pillars and show no clear signs of daily living, such as hearths or refuse pits. The inward-facing layout and careful placement of stones point towards gatherings of some importance. Many researchers see these structures as communal or ritual spaces, though the exact nature of their use remains uncertain.

Settlement evidence complicates early theories

For a long time, Göbekli Tepe was seen as a place people visited occasionally rather than lived in. This view has softened as excavation continued. Later work uncovered smaller buildings nearby and fragments of human bone, suggesting longer-term occupation in the surrounding area. The picture that emerges is not of a single-purpose site but of a broader landscape where people stayed, worked, and returned over generations.

Diet points to life before full agriculture

Even though there are indications that the site was used for a long time, the remains of farming at Gbekli Tepe are scarce. Most of the animal bones excavated at the site belong to wild species, mainly gazelle. Among the plant remains there were wild cereals instead of domesticated crops. This means that the people linked with Gbekli Tepe still depended on hunting and gathering for their food while they dedicated a lot of time and effort to the construction of their monumental buildings. They seem to be at a turning point, with a life, style halfway between nomadic and fully settled farming.

A carved boar drew attention in recent excavations

In 2023, scientists announced the finding of a life, size stone statue of a wild boar dating back to approximately 10, 500 years. It was discovered lying between the pillars and thus, it is assumed that it must have played a significant role inside the structure. Red, white and black pigments were found on parts of its surface, which leads to the assumption of the existence of colour and decoration that is now nearly totally missing on other parts of the site. Such discoveries provide us with more details about the site but at the same time, they leave us wondering.

Recognition brings protection and visitors

Göbekli Tepe was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 2018. Since then, it has become an important destination for visitors, with raised walkways and a dedicated visitor centre allowing access while protecting the remains. Excavation continues alongside tourism, moving slowly and deliberately. New findings tend to complicate rather than resolve the story.Göbekli Tepe does not overturn history in a single stroke. Instead, it presses gently against older timelines and assumptions. Its stones remain where they were set, offering clues without insisting on one explanation and leaving space for uncertainty to remain. Go to Source