Hollywood’s favourite lie about American power is not invasion. It is extraction. Invasion is loud, declarative, and visible. It requires Congress, allies, maps, speeches, and an architecture of justification that must be performed in public. Extraction, by contrast, is quiet. It happens at night, in borrowed uniforms, aboard aircraft whose tail numbers are never meant to be remembered. It runs on paperwork that exists only so it can later be shredded. Where invasion demands ownership, extraction promises deniability.This distinction matters because extraction allows the US to tell itself a comforting story. That whatever chaos it unleashed, whatever systems it destabilised or regimes it undermined, it still knows how to clean up after itself. Not the country. Not the wreckage. Just the people who matter.That is why modern American power, as imagined onscreen, no longer marches in. It slips out.

Take Zero Dark Thirty. Ostensibly, it is about killing Osama bin Laden. In practice, it is about exit velocity. The film does not end with the shot, or even with the body. It ends with Maya alone on a military transport plane, destination classified, mission complete, history compressed into a cargo hold. America arrives, does its dark work, and leaves without applause. Closure comes not from victory but from boarding.

Argo pushes the fantasy further by removing violence almost entirely. It turns a bureaucratic sleight of hand into a national epic. There are no bombs, no speeches, no heroic firefights. Instead there are forged documents, fake science-fiction scripts, and the quiet terror of a boarding gate that may or may not close in time. The extraction fantasy here is not martial. It is administrative. America does not win by force. It wins by forms, stamps, and the confidence to bluff while smiling.Together, these films establish the genre’s core promise. Things may be broken. Regimes may collapse. Allies may be abandoned. None of that is disqualifying. What matters is that the Americans will be retrieved. Eventually. If they are important enough.

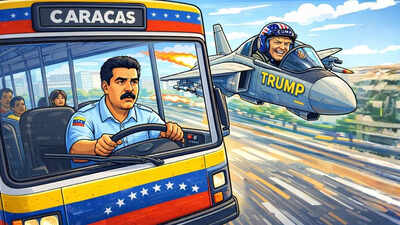

Television made this logic serial. In Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan, Venezuela becomes a playground for modern regime-adjacent thrill-seeking. Extraction is no longer a desperate last act. It is a recurring tactic. Helicopters arrive as punctuation marks. Diplomacy exists mainly to be bypassed. The CIA does not so much resolve crises as evacuate its protagonists from the consequences of their own involvement.The country itself remains unresolved, which is precisely the point. Jack Ryan does not imagine America fixing Venezuela. It imagines America surviving it.Older films were less coy about this instinct. Black Hawk Down presents itself as a war story about Somalia, but it is really a moral accounting exercise. The mission fails. Everything goes wrong. The city collapses into chaos. Politics evaporates. Somalis recede into scenery. And yet the film insists, relentlessly, on one principle alone: nobody is left behind. The Americans are recovered, one bloodied body at a time. Extraction becomes absolution.

The Cold War understood this logic early. Spy Game strips extraction of gunfire and replaces it with accounting. A single operative, abandoned years earlier in China, can still be saved if someone in Langley is willing to rearrange budgets, call in favours, and quietly bend rules. Power here is not tanks or bombs. It is institutional memory. It is knowing which lever still works at three in the morning.Even the bombastic entries follow the same grammar. Act of Valor dresses itself up as realism, but its true fantasy is competence without consequence. Every insertion is paired with an exit. Every door kicked open leads, eventually, back to the carrier deck. The world exists as a series of hostile rooms. America owns the hallway out.What makes this genre durable is not patriotism. It is deniability. Extractions are designed to be forgotten. They leave no victory parades, no occupations, no rebuilding phases. They end with rotors fading into the dark. This allows American power to remain emotionally clean even when it is geopolitically filthy.The same logic animates Clear and Present Danger, where covert wars in Colombia spiral far beyond control, yet the moral energy of the film is reserved almost entirely for rescuing abandoned US soldiers. The sin is not intervention. The sin is poor extraction planning. Fail to get your people out, and the system has malfunctioned.Television pushes this logic further still. In Homeland, asset extractions become tragic rituals. Sometimes they succeed. Often they fail. But the attempt itself is sacred. An asset may be tortured, broken, or killed, but the show insists on one thing: someone tried to pull them out. The empire’s conscience is measured in helicopters dispatched, not lives saved.The older mythologies were more honest in their delusions. Rambo: First Blood Part II does not bother with paperwork or plausibility. The extraction of POWs from Vietnam becomes pure wish-fulfilment, a fantasy that America never really lost because its men were simply left behind by weak politicians. Extraction here is retroactive victory, history rewritten through muscle.

Even theft becomes extraction. In Firefox, Clint Eastwood does not rescue a man. He steals a Soviet jet. Hardware itself is extracted, flown out of enemy territory as proof that American ingenuity can always reverse-engineer its way out of decline.Across decades, styles change. Enemies rotate. Technology improves. But the narrative constant remains. America may not fix the world, but it can still leave it. That is the quiet doctrine beneath the genre. Not Monroe. Not containment. Not even regime change. Extraction.It is a politics of exits, a worldview built on the assumption that global disorder is permanent, intervention is optional, and responsibility ends at the landing zone. Hollywood no longer sells American dominance. It sells American survivability. The helicopter lifting off at dawn is not just a cinematic trope. It is an ideology. Go to Source