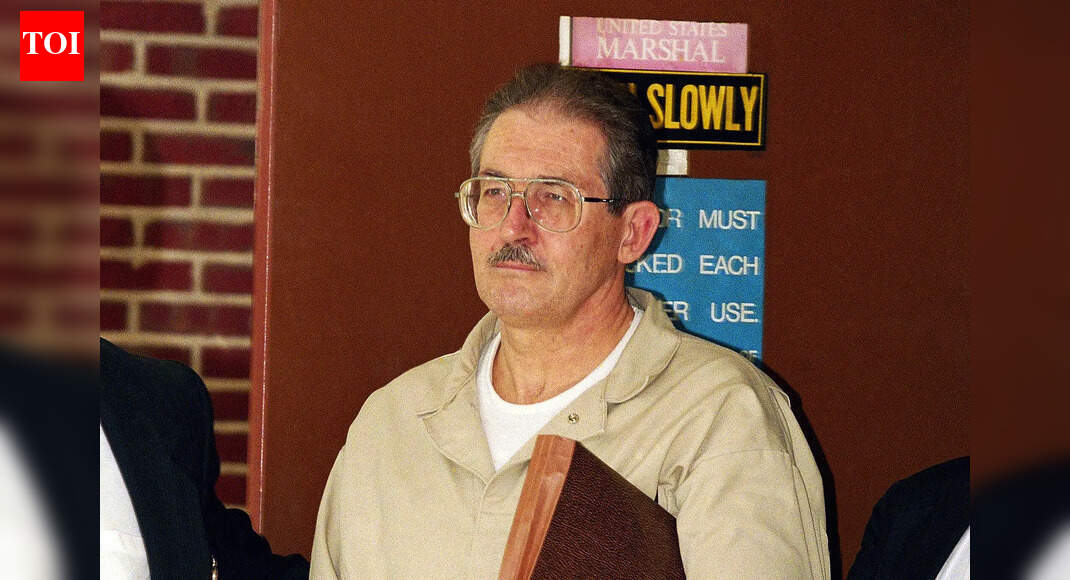

When Aldrich Ames finally left for the Elysian Fields, none of America’s major newspapers felt compelled to soften the landing. The New York Times called him what he was: “Aldrich Ames, C.I.A. Turncoat Who Helped the Soviets, Dies at 84.” The Washington Post went further: “the most damaging CIA traitor in agency history.” It was unduly harsh from a paper that once labelled ISIS chief Abu-Bakr Al-Baghddadi an austere scholar. That’s how deeply ingrained hate for Aldrich Ames is in the American psyche, the man who turned out to be a Russia’s most coveted asset during the Cold War. That unanimity tells you something important. Aldrich Ames is not remembered because he was fascinating. He is remembered because he was devastatingly ordinary.

The Alcoholic Traitor

To understand Aldrich Ames, one must first strip away the mythology that usually attaches itself to traitors. He was not glamorous, not especially clever, not driven by grand visions of history. He was, above all else, familiar. A second-generation CIA man who grew up inside the culture of secrecy, hierarchy, and quiet entitlement that defined Cold War intelligence work. His father had served in the agency and struggled with alcoholism, a detail often noted but rarely dwelt upon, even though it would quietly echo through the son’s life. Ames absorbed espionage not as a calling but as an atmosphere, something ambient and unquestioned. By the time he formally joined the CIA, intelligence work already felt less like a mission and more like an inheritance.What distinguished Ames early on was not promise but tolerance. He was repeatedly flagged as a mediocre field officer, better suited to desk work than clandestine operations. He drank heavily, performed unevenly, and carried himself with a resentful sense that the agency owed him more than it was willing to give. None of this stopped his rise. If anything, it made it easier. The CIA, confident in its own vetting and bound by institutional inertia, mistook longevity for reliability and familiarity for trust.By the early 1980s, Ames had reached a position of extraordinary sensitivity: counter-intelligence chief for the Soviet division. It was a role that granted him access to the deepest secrets of American espionage, including the identities of Soviet officials who had secretly chosen to work for the West. This was not the result of brilliance or strategic insight. It was the product of a system that promoted its own until there was no reason left not to.

The Non-Believer

Ames did not defect in a moment of ideological awakening. He unravelled. By the mid-1980s, his alcoholism had deepened into routine dependence. Vodka was not an indulgence but a stabiliser, a way of managing a professional life he felt increasingly unfulfilled by and a personal life that was collapsing under the weight of debt, divorce, and resentment. Money problems mounted. So did bitterness toward an agency he believed underpaid and underappreciated him. In 1985, with startling simplicity, he walked into the Soviet Embassy in Washington and offered himself. There was no gradual courtship, no coded overture. He handed over names, identified himself, and asked to be paid. The brazenness of the act was matched only by the speed with which it escalated.What followed was not a calculated long-term strategy but a panic-driven collapse of restraint. Ames feared exposure, particularly from the very Soviet assets he was responsible for protecting. His solution was annihilation. He betrayed them all, delivering to Moscow a comprehensive map of Western intelligence inside the Soviet system.Alcohol played a critical role here, not as an excuse but as an enabler. It dulled caution, eroded empathy, and encouraged the kind of compartmentalisation that allowed Ames to treat betrayal as a logistical problem rather than a moral one. He did not frame his actions as treason so much as transaction. Secrets became currency. Loyalty became irrelevant.The KGB understood what it had acquired. Ames was not a source of insight so much as volume, a bureaucratic funnel through which decades of American intelligence flowed directly into Soviet hands. For that, he was paid handsomely. Millions of dollars arrived, and with them came the lifestyle that Ames believed validated his choices.

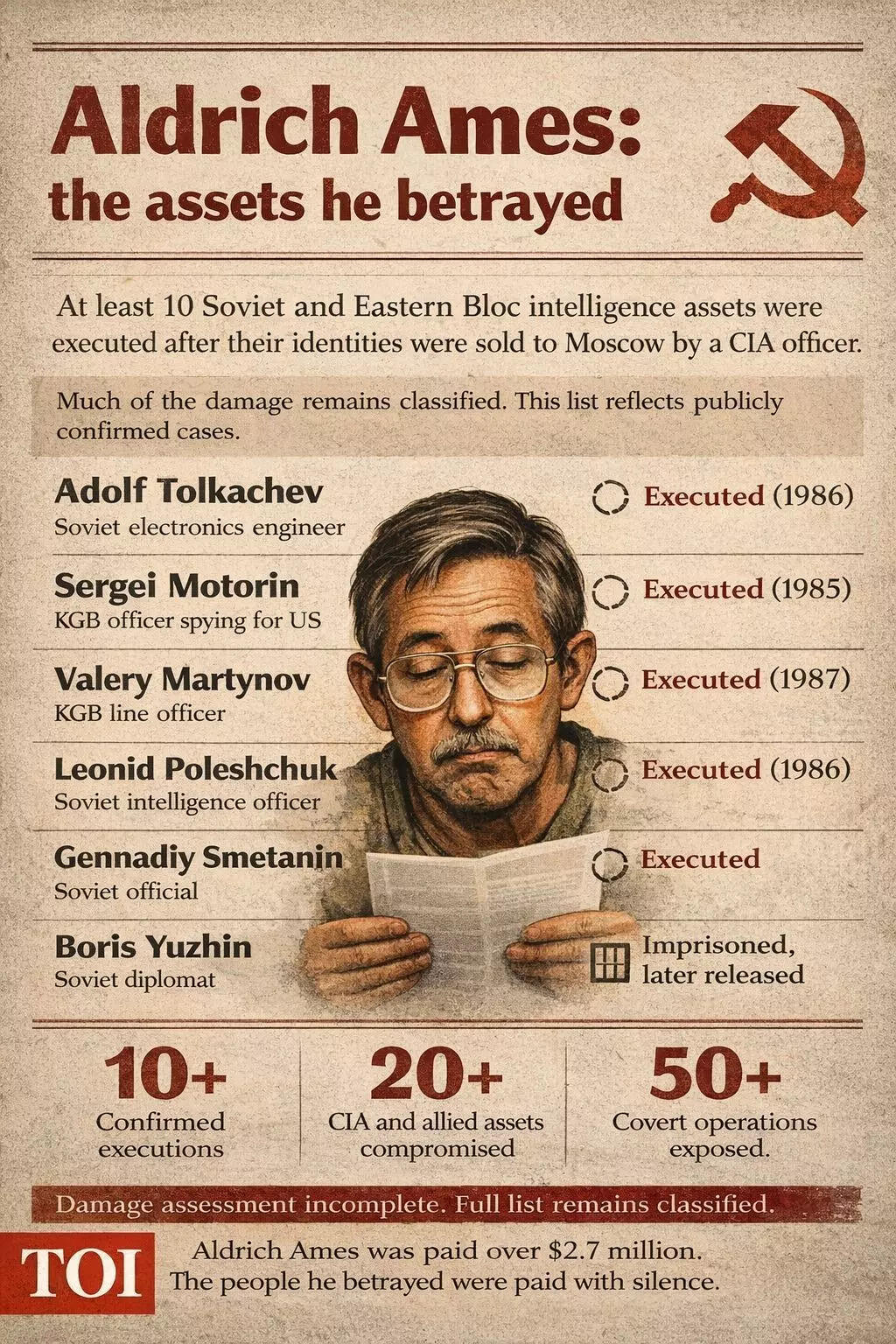

The Damage

The damage was immediate and catastrophic. As Ames’s disclosures reached Moscow, Soviet counter-intelligence moved swiftly. Western agents began disappearing. Some were arrested, others interrogated, and at least ten were executed. Networks that had taken decades to build collapsed almost overnight. The CIA lost its most valuable human intelligence channels at a moment when understanding the Soviet system was more important than ever.Beyond the human cost, which remains the most damning aspect of the case, Ames inflicted long-term strategic damage. The CIA’s picture of Soviet capabilities and intentions became distorted, increasingly reliant on technical intelligence and disinformation fed back through compromised channels. Policy debates at the highest levels of the US government were shaped by intelligence that was no longer trustworthy.Ames, confronted with the consequences, remained disturbingly detached. He insisted that espionage itself was overrated, that spy networks were theatrical exaggerations rather than essential instruments of statecraft. It was a view that conveniently absolved him of responsibility for the deaths that followed his actions. If the game was meaningless, then the pieces were expendable.This moral emptiness is what distinguishes Ames from ideological traitors of earlier eras. The Cambridge Five believed they were serving history. Ames believed nothing of the sort. His betrayal was not animated by conviction but by contempt, a corrosive belief that the system itself did not deserve loyalty.

Banality of Evil

What makes the Ames case especially damning is not how clever he was, but how long it took to notice what was obvious.By the late 1980s, his lifestyle had become impossible to ignore. He purchased a house in cash, drove a Jaguar, wore tailored suits, and paid for cosmetic dental work, all on a salary that could not plausibly support such spending. Colleagues noticed. Reports were filed. Investigations were opened and then allowed to stall.The CIA’s internal security apparatus moved with lethargy, hamstrung by understaffing, bureaucratic caution, and a culture that resisted the idea that one of its own could be responsible for such damage. At one point, the investigation was effectively paused when the sole officer assigned to it went off for training.It was only when the FBI took over that the pieces fell into place. Surveillance confirmed unexplained meetings and suspicious behaviour. Financial records told a story the agency had long refused to confront. In February 1994, Ames was arrested outside his home, ending nearly a decade of uninterrupted betrayal.When confronted, he pleaded guilty and accepted a life sentence. Even then, he downplayed the impact of his actions, insisting that the intelligence world exaggerated its own importance. It was a final act of deflection, consistent with a man who had spent years convincing himself that nothing truly mattered beyond his own survival. Go to Source