Pakistan’s latest surge of violence in Balochistan reflects a deepening, not isolated, security crisis as the Baloch Liberation Army escalates its campaign through “Operation Herof.”Driving the newsOver several days, the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA) unleashed what it calls “Operation Herof, Phase 2.0,” a wave of coordinated attacks across Balochistan that included suicide bombings, gun assaults and arson in major towns and remote districts alike.Pakistani authorities say dozens of civilians and security personnel were killed, followed by one of the largest counterterrorism strikes in decades. Officials claim more than 130 militants were killed in 48 hours alone. However, the BLA has refuted these official claims and reiterate that it inflicted severe casualties on Pakistan forces.What is clear: the scale, coordination and symbolism of the violence mark a sharp escalation in a conflict long treated by Islamabad as containable.

Why it matters

Balochistan sits at the intersection of Pakistan’s security, economy and foreign policy- and all three are now under strain. The province anchors China’s Belt and Road ambitions through the port of Gwadar, hosts globally significant mineral deposits at Reko Diq, and borders both Iran and Afghanistan at a time of regional instability.As analyst Michael Kugelman put it after the attacks, “Today’s attacks in Balochistan should serve as a wake up call to those… keen to invest in Pakistan’s critical mineral reserves.” He warned that many of those reserves lie in areas now directly hit by violence- and that resentment over “external exploitation of local resources” is central to the insurgency. For Islamabad, the stakes go beyond security. Investor confidence, relations with Beijing, and Pakistan’s credibility as a destination for critical minerals are all on the line.

The big picture

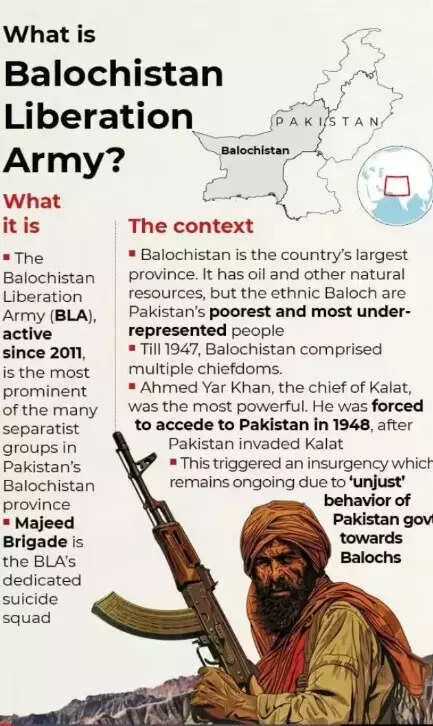

Balochistan’s troubles are hardly new, but they’re shiftingSince Pakistan’s birth, Baloch ethnic factions have, time and again, risen up against the central government. They’ve sought more autonomy, a larger share of the country’s wealth, or even complete independence. Each insurrection has been met with military force, temporary quiet, and, ultimately, unaddressed issues.

What’s different now is the interplay of three key factors:

First, economic importance. Balochistan is now crucial to Pakistan’s economic story. Think of the Chinese-funded projects and the West’s interest in copper, gold, and rare minerals.Second, political disillusionment. Elections since 2018 have been widely criticized, and the space for peaceful opposition has shrunk. This has intensified the feeling that political solutions are impossible.Third, the evolution of militant groups. Organizations like the BLA have become more dangerous, adept at using the media, and ideologically focused. They’ve adopted tactics from global insurgencies while staying rooted in local grievances.

Zoom in: What is “Herof”?

As per a report in the Native Voices: “Herof is a Balochi literary term meaning “black storm”, commonly used in Baloch poetry, including by the veteran poet Karim Dashti.”The BLA first used the term in August 2024, launching Herof 1.0 with attacks across 12 districts. That campaign shocked authorities by striking areas previously considered relatively stable, including Lasbela and Musakhel, and by introducing a female suicide bomber into the group’s operations.

Herof Phase 2.0 expands on that template:

- Geographic spread: Violence has been reported in Quetta, Noshki, Mastung, Kalat, Kharan, Panjgur, Gwadar, Pasni, Turbat, Kech and Awaran.

- Operational depth: Suicide bombings, vehicle-borne explosives and armed assaults occurred almost simultaneously.

- Human footprint: For the first time, women are reported to be participating in direct combat roles alongside men.

An intelligence officer cited by Native Voices estimated 800 to 1,000 fighters may be involved- a number that suggests months of recruitment, training and coordination.

What they are saying

Pakistani officials describe the violence as foreign-orchestrated terrorism.Balochistan chief minister Sarfraz Bugti said security forces killed 145 members of what he termed “Fitna al-Hindustan,” the state’s label for the BLA. He claimed militants aimed to seize hostages and storm government installations, and alleged backing from India and Afghanistan- accusations both countries deny.Residents recount chaos and fear. “(It) was a very scary day in the history of Quetta,” said Khan Muhammad, a local resident, describing armed men openly patrolling streets before security forces moved in.India’s foreign ministry rejected Pakistan’s claims, calling them “baseless,” and urged Islamabad to address “long-standing demands of its people in the region” instead of deflecting blame outward.

Between the lines

As per the Native Voices, the Baloch resentment has roots in a series of flashpoints.Several incidents hardened public anger: the killing of university student Hayat Baloch by paramilitary forces in 2020; the death of Malik Naz inside her home the same year; the crackdown on the Haq Do Tehreek protests in Gwadar; and the custodial killing of Baalach Mula Baksh in 2023. Each episode sparked protests. Each was followed by arrests, internet shutdowns, or worse.The arrest of activist Dr Mahrang Baloch in 2025 marked another turning point. To many young Baloch, her detention signaled that even peaceful dissent had become intolerable. Analysts say that belief has fed recruitment into armed groups, including among women, a shift now visible on the battlefield.Each episode narrowed political space- and widened the insurgency’s recruitment pool.As Kugelman noted, framing the crisis solely around body counts “telegraphs your policy failures- because the question is why are there so many fighters to start with.” Analysts argue the BLA has successfully tapped into accumulated resentment, especially among young Baloch who see peaceful activism punished and armed resistance rewarded with attention.

Zoom in: Bashir Zaib’s message

One of the most striking elements of Herof II has been its media choreography.As per the Native Voices, the BLA released new footage of its leader Bashir Zaib, seated on the back of a motorcycle, moving through rugged terrain believed to lie between Kharan and Chagai- a region synonymous with mineral wealth.Observers see layered symbolism: mobility, control and defiance. A senior Baloch journalist described the location choice as deliberate- close to Reko Diq and other high-profile mining sites that have drawn interest from companies like Barrick Gold and financiers such as the Asian Development Bank.The subtext to Islamabad and investors alike: the insurgency can operate where Pakistan’s economic future is being planned.

The regional angle

Timing matters.Analysts believe the BLA launched Herof II amid unrest in neighboring Iran’s Baloch-populated regions and persistent instability in Afghanistan to amplify its message beyond Pakistan’s borders.Balochistan’s long frontier with Iran- and proximity to Gulf shipping lanes- means sustained violence here resonates in Middle Eastern, US and European policy circles, particularly as Western governments search for alternatives to Chinese-dominated mineral supply chains.The message appears aimed as much at foreign capitals as at Islamabad.

What’s next

In the short term, security operations will intensify. Expect heavier troop deployments, stricter controls around mining projects, transport corridors and Chinese-linked infrastructure, and continued information blackouts during operations. Islamabad will likely double down on its claims of foreign sponsorship, even as evidence remains contested.The longer-term trajectory is murkier.The paradox facing Pakistan is stark: Balochistan is now too economically important to ignore- but remains too politically neglected to stabilize.Unless that gap is addressed, the “black storm” the BLA invokes may only deepen, reshaping the conflict from a peripheral insurgency into a central challenge to the state.

The bottom line

The spy-action film Dhurandhar has inadvertently revived global interest in the region by featuring elements that touch on Pakistan’s underworld and geopolitics set around Baloch communities.Dhurandhar revolves around a simple but unsettling idea: in covert conflict, what matters most is not the spectacle of action but the slow, almost invisible shifts beneath it. That logic offers a useful lens for what’s happening in Balochistan.Today, Balochistan can no longer be treated only as a security issue measured through attacks and casualties. It has become a political problem rooted in governance, representation, and legitimacy, and it cannot be managed through messaging, denial, or communication blackouts. Go to Source