A lot has been written about Scott Adams, the creator of the popular comic strip Dilbert, who passed away after a protracted battle with prostate cancer.The Washington Post’s eulogy, the same paper that once called Baghdadi an “austere scholar,” had the lede:“Scott Adams, who became a hero to millions of cubicle-dwelling office workers as the creator of the satirical comic strip Dilbert, only to rebrand himself as a digital provocateur — at home in the Trump era’s right-wing mediasphere — with inflammatory comments about race, politics and identity, died Jan. 13. He was 68.”

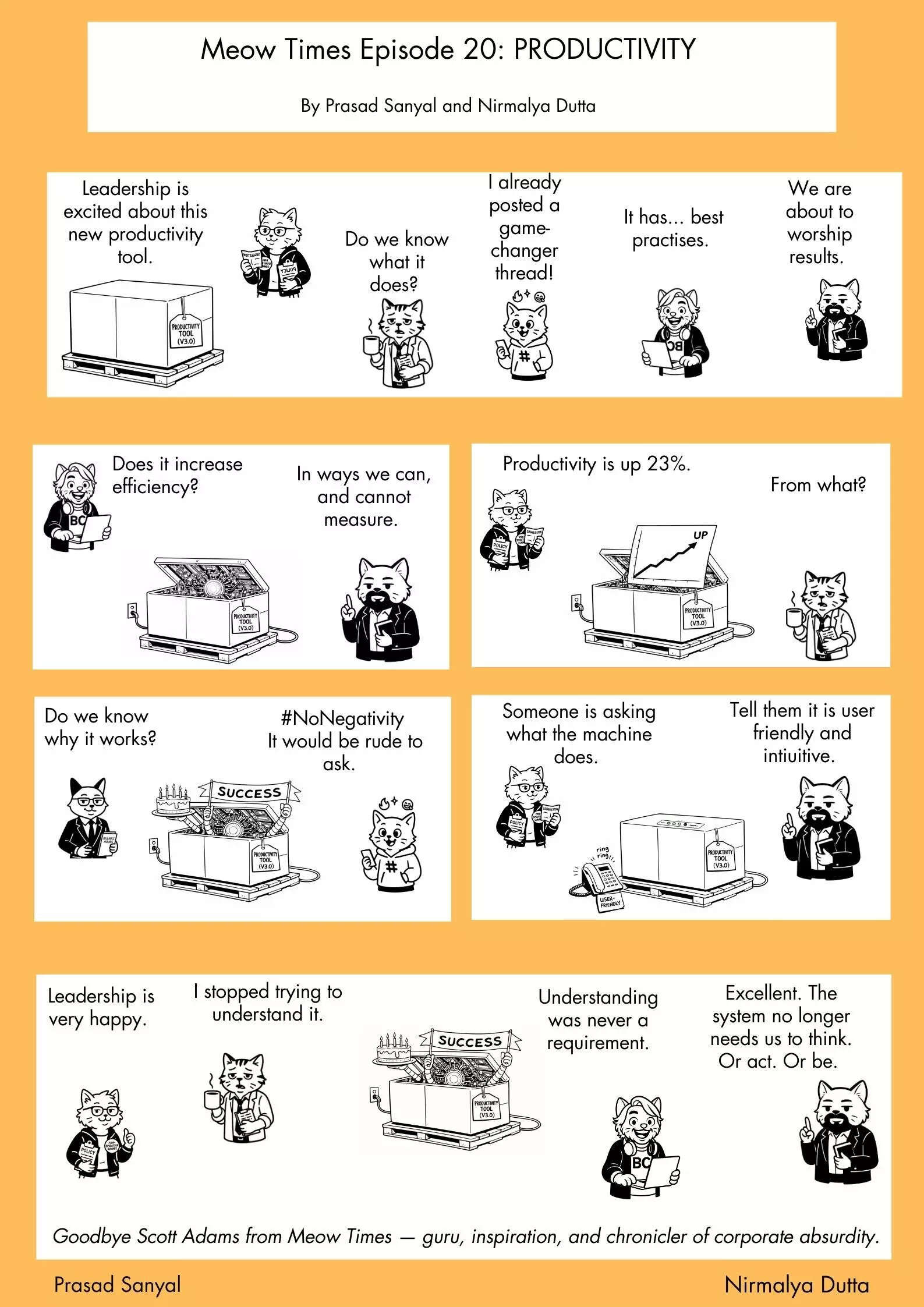

The New York Times obituary read: “Scott Adams, whose experience as a bank and phone company middle manager gave him the material to create the comic strip Dilbert, a daily satire of corporate life that became a sensation but was dropped by more than 1,000 newspapers after he made racist comments on his podcast in 2023, died on Tuesday at his home in Pleasanton, Calif., in the Bay Area. He was 68.”People magazine labelled him the “disgraced” Dilbert creator and, after online outrage, removed the author’s name altogether.But perhaps the best way to remember Scott Adams is through his own words.He once wrote: “I have poor art skills, mediocre business skills, good but not great writing talent, and an early knowledge of the Internet. And I have a good but not great sense of humour. I’m like one big mediocre soup. None of my skills are world-class, but when my mediocre skills are combined, they become a powerful market force.”And it was, as developers would call it, a full stack. Dilbert was remarkable simply because it was relatable. What made Adams unique was his firm grasp of the absurdity of the capitalist machine, which made Dilbert, in its own way, the ideological sequel to Yes Minister.Much like Yes Minister captured the absurdity of how bureaucracies function, Dilbert captured the intricacies of the institution that evolved from bureaucracies: the corporation.If Yes Minister showed the tussle between bureaucracy and the executive, Dilbert captured the fight between management, which wants all the credit, and employees, who end up with all the blame.Scott Adams drew on his own experiences to capture this absurdity.The Dilbert Principle started as a riff on the Peter Principle. The Peter Principle states that one rises to one’s level of incompetence in any corporate setup. The Dilbert Principle, at its core, holds that the most incompetent people are deliberately moved into management, where they can do the least damage.At its starkest, Dilbertism is not just a satire of office life. It is an accusation. It argues that modern corporations are not inefficient by accident but irrational by design. That they reward those who talk over those who think, those who manage optics over those who deliver outcomes. In the Dilbert universe, intelligence is a liability, competence is invisible, and clarity is career-limiting. Power flows not to the capable but to the unaccountable. What Adams captured, with brutal clarity, is that corporations do not fail despite incompetence. They often succeed because incompetence provides cover, hierarchy, and plausible deniability. Dilbertism is the recognition that the system is working exactly as intended. Just not for the people doing the work.

He amplified the absurdity with which incompetence thrives and is actively protected in corporate cultures; that meetings exist to distribute blame rather than create outcomes; that management language, even in the pre-GPT era, was designed to sound intelligent while conveying nothing. It captured the LinkedIn-post ethos of weaponised incompetence even before it existed.Consider some of his gems:

- Hard work is rewarding. Taking credit for other people’s hard work is rewarding and faster.

- The goal of management is not productivity. It’s plausible deniability.

- The purpose of a meeting is to create the illusion that something is happening.

- Engineers like to solve problems. If there are no problems, they will invent some.

- The appearance of competence is more important than competence itself.

- The trick to success is learning which rules matter and which ones don’t.

- Every system eventually evolves into one that rewards conformity over results.

Adams left for the Elysian plane after a protracted battle with prostate cancer. He continued to create Dilbert till his last days. On November 25 last year, he tweeted that his right hand had focal dystonia and his left hand was semi-paralysed, and that his art director would draw Dilbert while he continued to write it.Of course, Adams’ departure was only his second “death.” The first came in 2023, when his comic strip was dropped from syndication after he said that Black respondents who disagreed with the phrase “it’s okay to be white” constituted a “hate group.” His follow-up comment — “I don’t want anything to do with them and my best advice to white people is to get the hell away from Black people” — earned widespread condemnation. The strip was dropped by all major publications and effectively cancelled. Given his public support for Donald Trump since 2016, the rupture was perhaps inevitable.Adams’ political evolution was as controversial as it was deliberate. A long-time student of persuasion, hypnosis, and narrative framing, he supported Trump early not because he admired Trump’s morality or governance, but because he believed Trump to be a master persuader who intuitively understood media dynamics better than his critics. Adams repeatedly argued that politics was not about policy but about storytelling, emotion, and perception. He dismissed traditional fact-checking as politically irrelevant and described modern voters as driven more by narrative resonance than empirical truth.Over time, this worldview hardened into a contrarian, often abrasive stance on race, identity politics, gender, and institutional trust. He framed himself as anti-woke, anti-establishment, and sceptical of elite consensus, positioning his provocations as “clarity” rather than cruelty. Critics saw a man sliding into grievance politics; Adams saw himself as a diagnostician pointing out uncomfortable truths about persuasion, power, and social fracture. Whether one agrees or not, his political commentary followed the same pattern as Dilbert: reduce complex systems to their ugliest incentives and then laugh at the result.

Adams’ comments raise a perennial question about creators: should we remember them for the work they brought into the world or the magic they created through it? Either way, Adams would have found it funny. Adams once made a caustic yet accurate observation about civilisation. Explaining how the printing press ensured that no good ideas ever truly died, he wrote: “We are a planet of nearly six billion ninnies living in a civilisation that was designed by a few thousand amazingly smart deviants.”He elaborated: “All the technology that surrounds us, all the management theories, the economic models that predict and guide our behaviour, the science that helps us live to eighty — it’s all created by a tiny percentage of deviant smart people. The rest of us are treading water as fast as we can.”His favourite example to buttress the point: “True example: Kodak introduced a single-use camera called the Weekender. Customers have called the support line to ask if it’s okay to use it during the week.” The word “genius” is used with wanton abandon these days, but it fits Scott Adams. He was not one of the deviants who designed civilisation, but he was one of the few who explained it to the ninnies trapped inside it. In doing so, he turned confusion into clarity, frustration into laughter, and work into something survivable. That, too, is a civilisational contribution. Because without art, are we even human? Go to Source