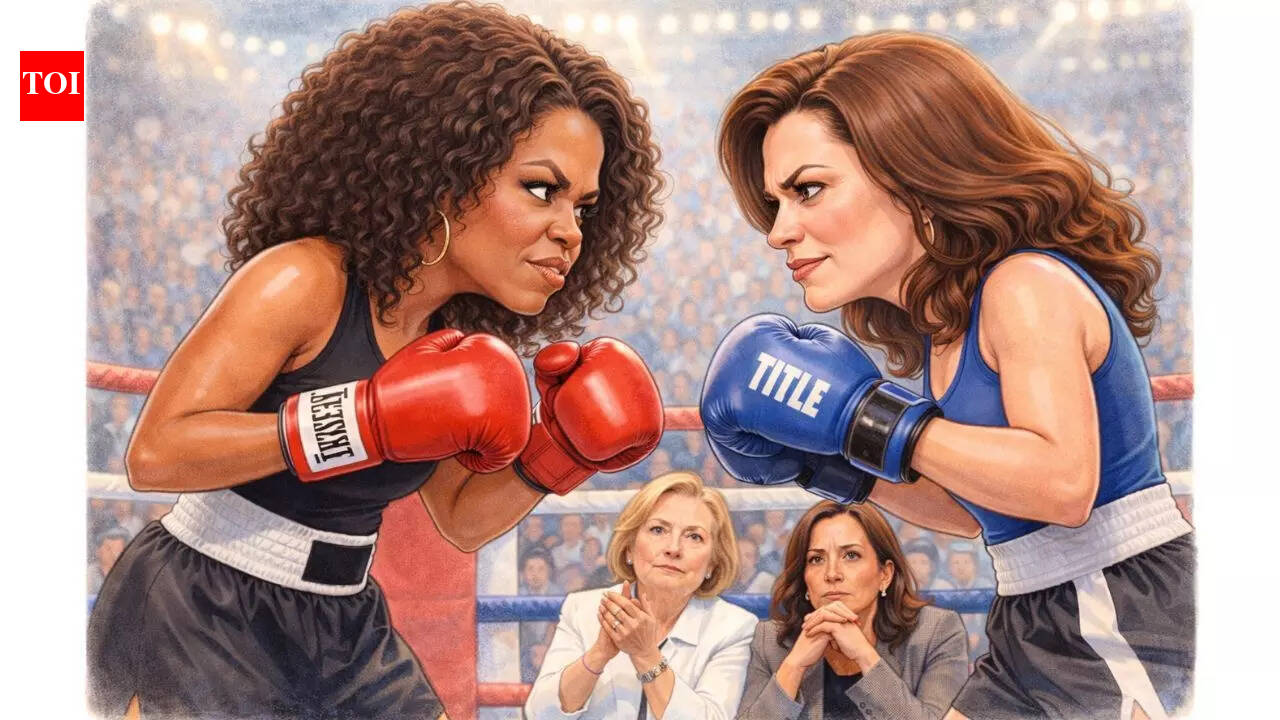

For nearly a decade, Democrats have handled defeat like something fragile and embarrassing, preferring to step around it rather than examine it, until two women finally spoke with a clarity the party has long avoided.Michelle Obama said aloud what many Democrats have privately suspected but rarely admitted during an election cycle. “There are men out there that were not going to vote for a woman,” she said. “Let’s just be real about it and let’s put that on the table.”Gretchen Whitmer rejected that conclusion outright, arguing that the country is not frozen in that moment of prejudice. “I think America is ready for a woman president,” she said.What appears to be a disagreement between two prominent voices is, in fact, a delayed reckoning over how Democrats explain their own losses and how much responsibility they are willing to accept for them.Obama’s view is shaped by electoral memory rather than abstraction. The defeats of Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Kamala Harris in 2024 still loom over the party, particularly because both contests ended with victories for Donald Trump. From that perspective, Obama’s argument is not that sexism explains everything, but that it explains enough to make denial untenable.Whitmer’s disagreement is not with the existence of bias but with the fatalism that flows from it. Her argument rests on the reality of modern electoral politics, in which women continue to win governorships, Senate races and statewide offices across the country, suggesting that voters are not rejecting female leadership as a category but responding to individual candidates and campaigns.That distinction matters because the Democratic Party has spent much of the post-Obama era avoiding serious internal confrontation. After Barack Obama left the White House, the party increasingly prioritised coalition management over ideological clarity, smoothing over disagreements rather than resolving them. The 2016 decision to clear the field for Clinton at the expense of Bernie Sanders left questions unanswered, and the arrival of Trump soon after pushed Democrats into a permanent defensive crouch focused on protecting norms and institutions rather than interrogating their own failures.The consequence was a party that reacted continuously but reflected rarely, and that pattern resurfaced in 2024.

What went wrong with Kamala Harris

Harris did not lose because she lacked experience or qualifications, but because too many voters struggled to understand what she represented in a moment defined by economic anxiety and political frustration. Her campaign oscillated between presenting itself as a continuation of the administration’s work and signalling the need for course correction, which left her message blurred rather than broadened.At a time when inflation, cost-of-living pressures and border concerns dominated the electorate’s priorities, Harris spoke in detailed policy terms while many voters looked for a clearer sense of direction and conviction. She also carried the weight of an administration that a significant portion of the electorate felt uncertain about, without fully owning its record or decisively separating herself from it.Sexism played a role in shaping perceptions, but strategy and clarity mattered as well, and pretending otherwise only postpones the lesson.This is why the exchange between Obama and Whitmer matters. Obama is insisting that Democrats confront voter bias without comforting illusions, while Whitmer is insisting that the party confront its own strategic shortcomings without retreating into inevitability.