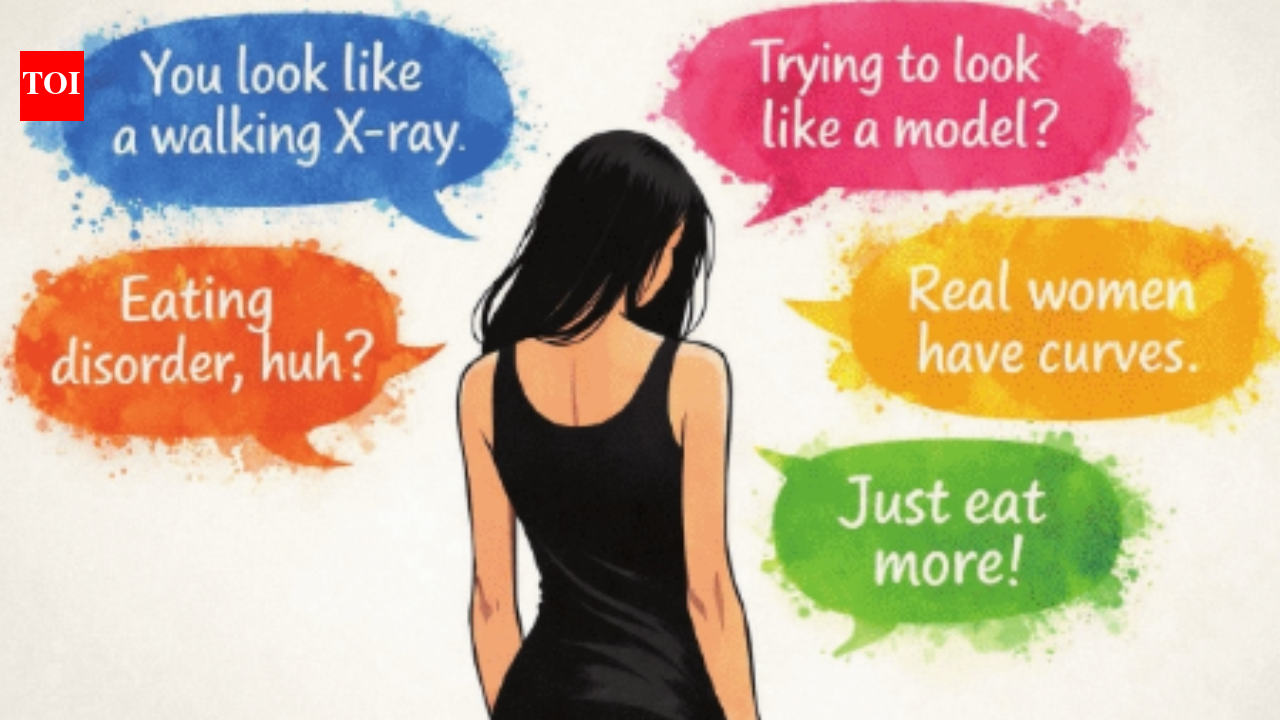

“How are you a Bengali girl if you don’t have a round chubby face?”“Careful on the terrace or the wind may blow you off…”“Do you need a belt, or will a rubber band do?” “Sure it’s not anorexia?”Over the years, I’ve heard them all. Sometimes, all in the same afternoon. Usually delivered with a laugh. Always a laugh. Which seems to make it acceptable.Being thin comes with a peculiar licence for casual body policing. Despite a culture that idolises skinny bodies plastered across popular media, thinness turns out to be desirable in theory and rather suspect up close. We celebrate it on runways and screens, then mock it in real life.Let me clarify. I never quite fitted the Bengali stereotype of women with soft, rounded curves or the cherished idea of looking visibly ‘well-fed’ on ‘maach bhaat’. I was born thin, stayed thin, and now in my forties, still thin. Not because I’m trying to “maintain” myself, as many assume but because my metabolism has perhaps always done its own thing.Contrary to popular belief, I eat. Well. Often. With enthusiasm. I’ve never dieted, chased size-zero, or feared carbs. I binge on cheese and fries when the mood strikes and accept second helpings of samosa-jalebi from well-meaning friends determined to “fatten me up”. I am also routinely informed that lean women are objects of envy. So far, so good.Except that this is where the compliments end and the comments begin.It started before I was old enough to register it. Standing out in a family of rounded figures, relatives wondered aloud if something in my genes had gone astray. In my teenage years, someone called me a “toothpick”. It took me twenty years to realise this had a name: thin shaming. At the time, it was just one of many things said casually, jokingly, even affectionately. “Bag of bones”, “matchsticks”, “twiggy”, “walking X-ray”.Even after ‘skinny shaming’ entered public vocabulary, the repertoire merely evolved. “Are you ill or something?” “How long will you diet?” And occasionally, for variety, “Trying to become a model?” said aloud at family gatherings, classrooms and later, offices.Because here’s the thing. You wouldn’t call someone fat to their face anymore. We’ve been trained out of that, at least socially. But calling someone “too thin” is still fair game.I’d usually let these jokes land. But once, a distant relative surveyed me at a family dinner and announced, with the solemn air of a doctor, that I resembled a skeleton, apparently concerned that I wasn’t eating enough. I smiled sweetly and suggested she looked rather like a baby elephant. She was offended. I was lectured on sensitivity.What surprised me though was when she apologised later. It had finally occurred to her how casually offensive her own remark had been.Pray, why are there bodies you protect, and bodies you’re allowed to comment on freely?And sometimes, it doesn’t stop at words. A woman at a party I was acquainted with conducted a quick inspection of my midriff, tugging at the band of my dress to check if I was wearing a body shaper. When her investigation yielded nothing, she laughed and asked if I even had a stomach.Another time, a consulate official insisted on carrying my plate at a reception. I mistook it for old-school courtesy until he winked at how “tiny” I was. I stood there plate-less, weighing whether to thank him, laugh along, or recoil.Complete strangers — at a train station, during a spa therapy, in a theatre loo — have offered meal plans I never asked for. People also feel entitled to audit what you eat, when you eat, and how much makes it from plate to mouth. If you’re having a salad, there must be an eating disorder. If you skip dessert, someone will insist you fear calories. If you go for it, it’s followed by a triumphant, “Good, you need it.”Strangely, after all that caring, thin is automatically deemed fit. And fine. Lucky, even. Any health complaint is dismissed as exaggeration or attention-seeking. “Just eat more,” they say, because any anomaly is self-inflicted or worse, imaginary.Once, an undiagnosed allergy spiralled because my symptoms were dismissed as a side effect of being skinny and “not eating enough”. I was handed a food chart. The allergy worsened. What makes this harder is that it’s rarely acknowledged as harmful.Popular culture hasn’t helped either. I have a yawning dislike for that cheerful body-positive Meghan Trainor song that announces it’s “all about that bass” while swatting skinny women as fake, silicone stick figures no man should possibly want.Which brings me to the deeply irritating ideal that ‘real women have curves’. I’ve always found this baffling. Since when did fat percentage become a qualification for womanhood?By now, I’ve also learnt that no one steps in when thin-shaming happens openly right in the middle of a dinner table or a group chat. Not because people are brutal but because they don’t think it’s unkind. Skinny shaming survives because it doesn’t sound like an insult. It sounds like banter, teasing or a backhanded compliment from someone “only joking” or “just worried about you.”The irony is relentless. This is what pop culture has long sold as “the goal”. The XS silhouette is what runways are built for and AI churns out by the million, and now the Ozempics and Mounjaros promise. And yet, I’ve spent a lifetime feeling awkward inside a body everyone assumes I must love. I do — quite unapologetically — even as I’m habitually guilt-tripped for it.A new AIIMS-ICMR study has finally put numbers to what many like me have lived. Conducted among 1,071 young adults aged 18-30 attending AIIMS outpatient clinics, it found that 47% of underweight participants reported moderate to severe body image distress, almost as high as the 49% reported by those with obesity.I’m outside that age bracket now and don’t get angry anymore. Mostly, I get tired. Tired of explaining my metabolism, justifying my appetite, reassuring people that my blood reports are excellent, of hearing “I wish I had your problem” from people who don’t see it as a problem at all.I’ve even curated a bagful of skinny jokes over the years and now ask folks to get more creative when they reach for the hackneyed gags about being blown away by a chance breeze. Somewhere along the way, I reclaimed my right to decide what my body is and is not.But not everyone can. And that’s the part we don’t talk about. Go to Source