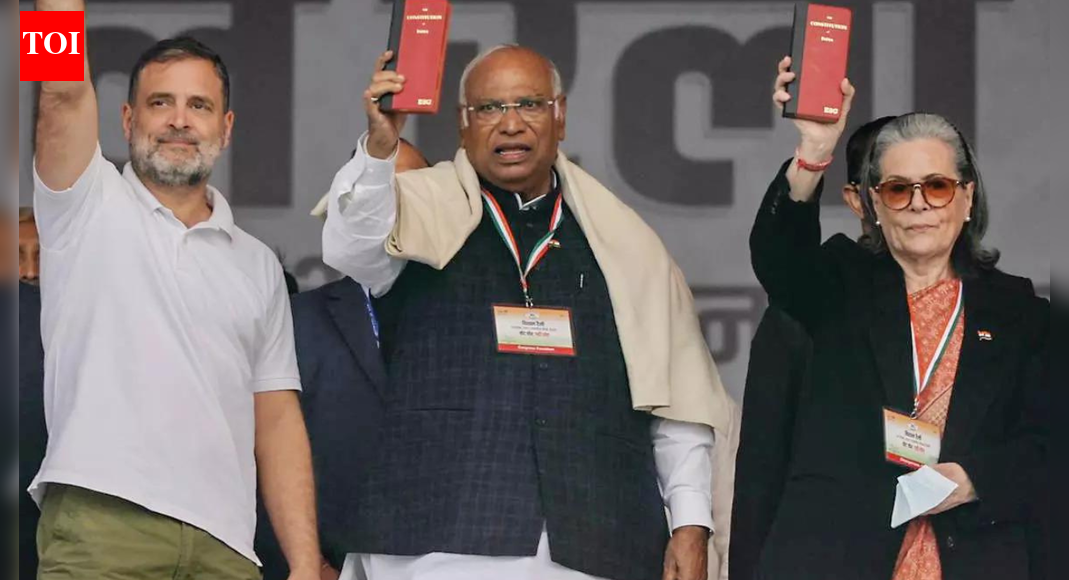

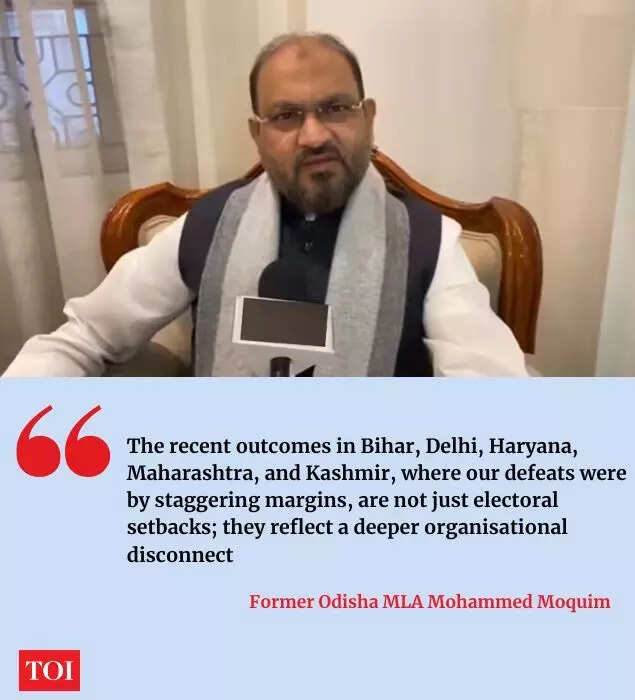

NEW DELHI: The Congress’s internal churn burst into the open again this week after former Odisha MLA Mohammed Moquim wrote to Sonia Gandhi, calling for “open-heart surgery” in the party and flagging a growing disconnect between the leadership and its workers.Similar concerns were raised in the run-up to the Bihar assembly elections this year in November, where the distance between the “leadership” and the workers was on display during seat distribution talks.Since its formation in 1885, the Congress has had plenty of plenty. There were too many popular leaders, too many dedicated party workers and too many loyal supporters during the country’s freedom struggle.After Independence, the country rallied behind Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and the Congress, helping the party win almost every election. To its credit, the party served as a broad canopy under which different ideologies co-existed.Cut to the run-up to the 2014 Lok Sabha election: everything seemed to go against the grand old party. After a 10-year run at the Centre, the Congress found itself reeling under corruption charges, anti-incumbency and a sudden exodus of senior leaders just ahead of the polls. The final nail in the coffin was the “Modi wave”, which helped the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) sweep away the general election. Since then, the stars have not aligned for the Congress. The party continues to face more or less the same problems it did a decade ago. It remains plagued by infighting, disillusioned workers and senior leaders jumping ship after flagging serious leadership issues.On December 8, ex-Odisha MLA Mohammed Moquim pointed to six consecutive election losses while also questioning the selection of Mallikarjun Kharge as the party’s leader, claiming that the 83-year-old veteran “is unable to resonate with India’s youth.

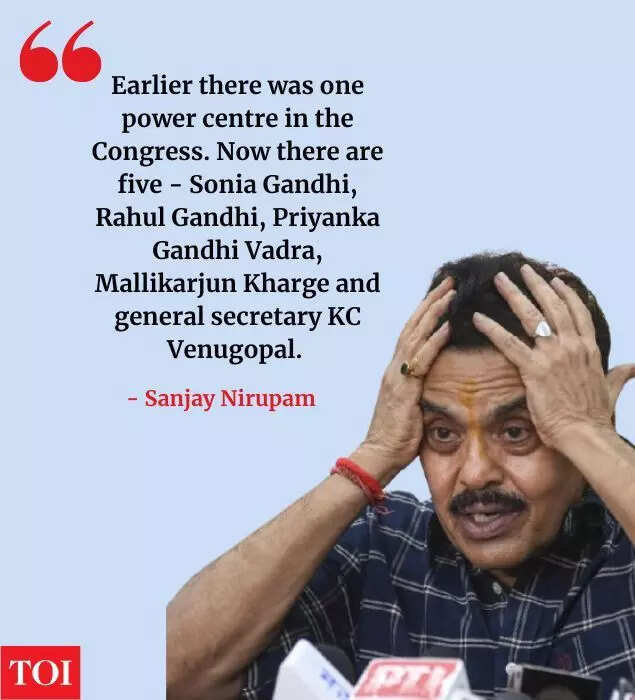

In his five-page letter, he also complained that he had not been granted an audience with Rahul Gandhi for almost three years. “This is not a personal grievance … but a reflection of a wider emotional disconnect felt by workers across India, who feel unseen and unheard,” he wrote.This is not the first time a party leader has complained about not getting an audience with the Congress scion. The list has only grown longer. Leaders such as Himanta Biswa Sarma, Jyotiraditya Scindia, Ghulam Nabi Azad and Jitin Prasada have quit the Congress and joined rival parties after raising similar concerns.This raises a key question: why are so many leaders disgruntled with the grand old party, and why is it steadily losing its cadre across states?Defeats after defeatsAfter suffering a debacle in the 2014 general election at the hands of the BJP, the Congress has lost more elections than it has won. Even after a promising performance in the 2024 Lok Sabha polls, the party soon lost steam. The sharpest slide came in the Maharashtra Assembly elections, where the Congress was reduced to just 16 seats. In Bihar, its tally halved from 12 to six, while in Haryana – where it hoped to convert Lok Sabha momentum into victory – it slipped from 42 to 37. Even in Delhi, where the Congress was trying to claw back to relevance, the party drew a blank for the third consecutive time.The only two states where the Congress did marginally better – Jammu & Kashmir and Jharkhand – were ones where it fought as a junior partner in a coalition.Unholy marriagesIn political alliances, chemistry between parties is paramount. Historically, however, many regional parties allied with the Congress were either born out of splits from it or emerged from anti-Congress sentiment.This unequal match often creates friction for the grand old party. For instance, the Congress’s alliance with the National Conference in Jammu and Kashmir appeared to be on the brink of collapse following sharp differences.Chief minister Omar Abdullah has, on several occasions, publicly expressed displeasure over the Congress’s decision to launch a campaign for the restoration of statehood without consulting its ally.Similarly, the Congress’s relationship with the Aam Aadmi Party has been turbulent within the INDIA bloc. After prolonged seat-sharing negotiations and resistance from the Congress’s Delhi unit, the two parties fought together in Delhi, Gujarat and Haryana in the Lok Sabha polls, but against each other in Punjab.Last year, they failed to reach a consensus on seat-sharing in the Haryana Assembly elections and contested separately. In the Delhi Assembly elections earlier this year as well, both parties fought a bitter battle, raising questions over how the two would function as allies within the INDIA bloc.In such situations, party workers on the ground – wired to defend their own party – often find themselves confused while coordinating with alliance partners who hold opposing ideological positions.Decisions by the ‘high command’The Congress ‘high command’ is also frequently accused of taking too long to act when power tussles erupt within state units.As an ongoing standoff between Karnataka chief minister Siddaramaiah and his deputy DK Shivakumar forces the leadership into repeated deliberations, no decisive call has yet been taken.Similar leadership tussles played out in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, where factionalism among state leaders eventually contributed to the party losing power. The common thread across these states has been the Congress leadership’s reluctance to act decisively in battles between the old guard and younger turks.In Rajasthan, Sachin Pilot – who as state president had led the party to a decisive victory in 2018 – staked claim to the chief minister’s post. The party, however, backed veteran Ashok Gehlot, who had led the Congress to defeat in 2013. Pilot and his supporters were left disappointed. When he intensified his campaign for the top job, Gehlot used his influence to quell the rebellion. Though the Gandhi family persuaded Pilot to stay, the high command’s bet on Gehlot failed, with the party losing the state in 2024.Who is the high command, anyway?Several Congress leaders, including Sanjay Nirupam, have alleged that the party suffers from multiple power centres, each backed by its own lobby.Expelled from the party in 2024, Nirupam claimed there was no future for the Congress and accused the leadership of “tremendous arrogance”.

“Earlier there was one power centre in the Congress. Now there are five – Sonia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi, Priyanka Gandhi Vadra, Mallikarjun Kharge and general secretary KC Venugopal. All have their own lobbies, which keep clashing. In the middle of this, lakhs of workers like me are stuck,” Nirupam had said.Rahul Gandhi’s fading charmIn the Bihar Assembly elections, Rahul Gandhi once again failed to make an impact. His Voter Adhikar Yatra, launched just days before polling, did not turn out to be the trump card the party was hoping it would. His repeated attacks on the Election Commission and allegations of “vote theft” also failed to resonate with voters.After the yatra, Rahul remained largely absent, returning to the campaign trail only in the last leg. His absence became a major issue amid unrest within party ranks, with leaders alleging discrepancies in ticket distribution.As the polls approached, cracks within the Congress’s Bihar unit resurfaced. Rebel leaders, including several MLAs, staged protests after being denied tickets and demanded the immediate replacement of the party’s Bihar in-charge, Krishna Allavaru, with a “political” appointee. As expected, the writing was on the wall and the party emerged as the weakest link in its alliance, recording the lowest strike rate among the major partners. The Congress seems to be mired in a cycle of post-mortems, exits, and letters for the time being, while its rival BJP is busy expanding its presence on the ground. As the five states/UT, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Assam, Kerala and Puducherry, gear up for the high-stakes elections next year, the real test no longer remains about winning for Congress, but whether the party can still reform itself in time. Go to Source