As the dust settles into 2025, Parliament carries forward unfinished business, unresolved disputes and reforms still searching for their final shape.The Winter Session restructured key pillars of governance, but several high-stakes bills were deferred, diluted or sent for further scrutiny.The Budget Session of 2026 is expected to move beyond diagnosing problems to implementing solutions — laying out the governing blueprint for the government’s vision of “Viksit Bharat”.With a focus on higher education reforms, electoral synchronisation, capital market restructuring and insolvency resolution, the Budget Session of 2026 sets the stage for high-stakes legislative action.

What carries forward into 2026

While the government pushed through several landmark reforms during the Winter Session, many bills were formally introduced but ran into procedural hurdles.Several were referred to Joint Parliamentary Committees or held back for further refinement, effectively shifting the legislative battleground to the Budget Session of 2026.

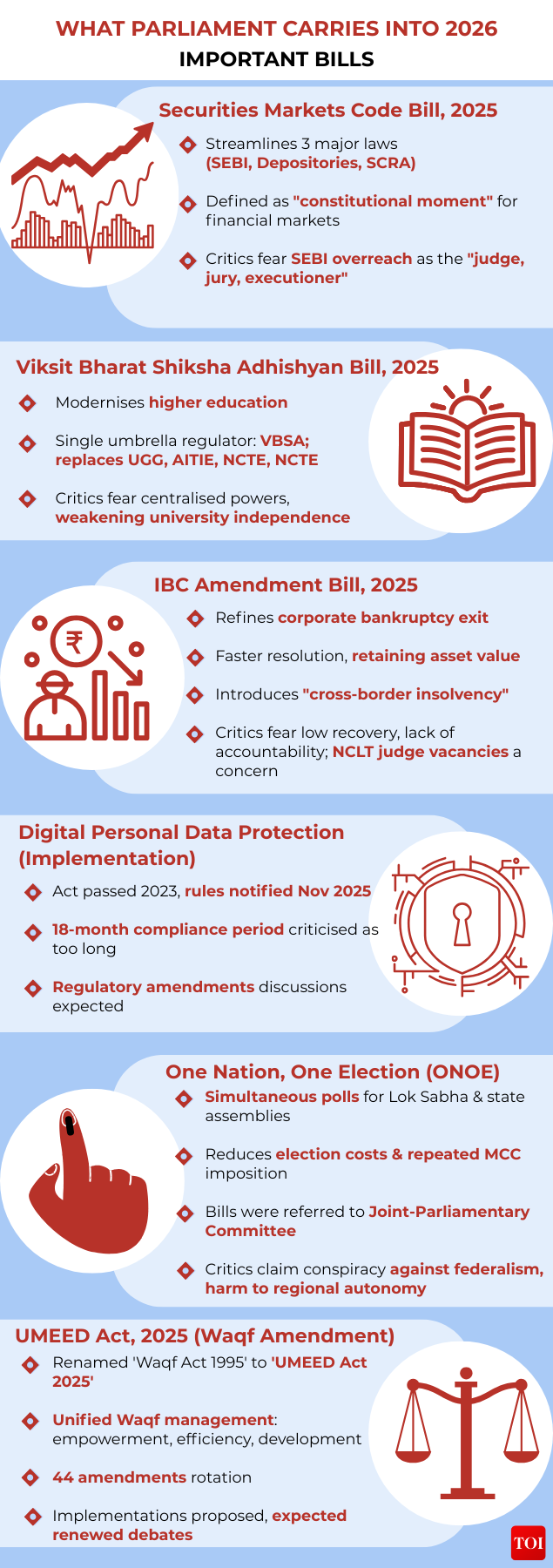

Securities Markets Code Bill, 2025

Hailed by the government as a “constitutional moment” for India’s financial markets, the bill seeks to streamline three major laws governing investors and market regulation.For over three decades, investors and companies have navigated three separate laws — the SEBI Act (1992), the Depositories Act (1996) and the Securities Contracts (Regulation) Act (1956). Given its scale and potential impact on trillions of rupees in market wealth, the bill was referred to the Standing Committee on Finance in late 2025 for detailed scrutiny, before it returns to Parliament in 2026.Critics argue that merging these laws risks turning SEBI into “judge, jury and executioner”, with sweeping enforcement powers.The government, however, has argued that unified regulation is essential to reduce overlap, regulatory arbitrage and compliance confusion in a rapidly expanding market.

Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) Amendment Bill, 2025

The bill seeks to fine-tune India’s corporate bankruptcy exit framework.The bill aims to make the resolution faster so that companies do not lose the value of their assets during long legal proceedings. It also introduces a “Cross-Border Insolvency” framework to help banks recover money from defaulting companies that have hidden or kept assets in foreign countries.Critics argue that banks take big losses in recovering a very small percentage of the original loans, and that the bill does not hold the big promoters accountable enough.They also highlight the pending judicial cases in the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) due to vacant judges’ seats for the proceedings.Opposition has also flagged delays caused by vacancies in the National Company Law Tribunal, arguing that legislative fixes alone cannot address systemic capacity gaps.

One Nation, One Election (ONOE)

The One Nation One Election (ONOE) reform proposes to hold simultaneous elections for the Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies, consolidating the voting process to occur at the same time instead of staggered intervals.The government initiated this plan in late 2024 with the introduction of the Constitution 129th Amendment Bill. While the bill gained majority votes in the Lok Sabha, it was not passed. This is because amending the Constitution requires a special majority where at least two-third of the members present in the House must vote in favour of the bill.The Lok Sabha approved a motion to refer both the two bills that shall pave the way for “one nation one election” to a 39-member Joint Parliamentary Committee. This committee has been granted an extension to submit its report until the first day of the last week of the Budget Session 2026.The primary objective of the bill is to conduct simultaneous elections—initially for the Lok Sabha and State Assemblies, and later potentially for local bodies—to reduce election expenses and prevent the repeated imposition of the Model Code of Conduct.The opposition rejected the bill as a “heinous conspiracy” against federalism, arguing it assaults the Constitution’s basic structure and undermines regional autonomy.

Viksit Bharat Shiksha Adhishthan Bill, 2025

The bill is the main part of the government’s plan to modernise higher education by bringing several regulators under one system.It was introduced in the Lok Sabha on December 15, 2025, and was later sent to a Joint Parliamentary Committee, the report of which is expected to be presented by the last day of the first part of the Budget Session 2026.The bill proposes setting up the Viksit Bharat Shiksha Adhishthan, or VBSA, as a single umbrella regulator, meaning one main authority that will replace UGC, AICTE, and NCTE. The government has described this system as one with fewer controls but strict enforcement, in line with the National Education Policy 2020.The opposition, however, argued that it gives too much power to the Union government and could weaken the independence of universities, especially because the power to give financial grants will shift from the regulators to the ministry.

Digital Personal Data Protection (Implementation)

Although the Digital Personal Data Protection Act was passed in 2023, it came into effect only in late 2025, when the government notified the detailed rules needed to put it into practice.The rules were officially notified on November 14, 2025, after wide public consultation.With implementation now underway, parliamentary oversight is expected on regulatory amendments, institutional capacity and funding for the Data Protection Board.Also, while the law itself was already in force, civil society groups and opposition voices focused their criticism on the rules, especially the 18-month compliance period, which they felt was too long and delayed real protection.

UMEED Act, 2025 – Waqf (Amendment) Act

One of the most socially and politically sensitive legislations in recent sessions, the bill was first introduced in August 2024 and was swiftly referred to a Joint Parliamentary Committee following widespread protests.The committee, chaired by Jagdambika Pal, submitted its final report in late January 2025 after several contentious meetings. The report recommended mandatory registration of all Waqf properties on a centralised online portal and proposed 44 amendments to the original Waqf Act of 1995.The legislation introduces multiple legal changes, including renaming the Waqf Act as the UMEED Act — the Unified Waqf Management, Empowerment, Efficiency and Development Act, 2025.While the bill is not formally listed on the agenda for the Budget Session of 2026, its implementation, set to begin this year, is expected to trigger renewed uproar.At its core, the legislation seeks to overhaul the governance and management of Waqf properties across the country.

Bills that passed: A session of disruption and overhaul

If Parliament were a 75-year-old house, the 2025 session resembled a noisy renovation. The government did not limit itself to cosmetic changes: labour laws were reworked, nuclear policy rewired, welfare delivery redesigned and decades-old statutes discarded. The result was a modernised legal framework — albeit amid sustained protest.With debates over worker rights, accountability and foreign participation dominating proceedings, the session concluded with several laws passed, but left many political and social questions unresolved as Parliament heads into 2026.

VB–G RAM G Bill, 2025: Welfare reset

Replacing MGNREGA, the VB–G RAM G Bill — Viksit Bharat–Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) — was tabled on December 15, 2025, and passed three days later through a voice vote amid opposition demands for a recorded division.

The law increases guaranteed workdays from 100 to 125 annually but introduces fixed, state-wise allocations, replacing MGNREGA’s demand-driven funding model. Critics argue this risks weakening the programme’s role as a distress buffer.The removal of Mahatma Gandhi’s name became a major flashpoint, alongside concerns over the use of AI and biometric attendance systems that could exclude workers in low-connectivity areas.

SHANTI Bill, 2025

Passed by voice vote in both Houses, the SHANTI Bill replaces the Atomic Energy Act (1962) and the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act (2010), allowing private and foreign participation in nuclear power generation.The law grants statutory status to the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board and clears the path for small modular reactors. Opposition parties staged a walkout, objecting to diluted supplier liability provisions and warning that public risk would shift to the state in the event of an accident.

Sabka Bima Sabki Raksha Bill

Passed on December 16, 2025, the bill raises FDI limits in insurance from 74% to 100%, aiming to achieve universal insurance coverage by 2047.While the government argues this will deepen penetration and reduce costs, critics warn of foreign dominance, reduced focus on rural markets and potential pressure on domestic players like LIC.Health & National Security Cess BillUnanimously passed, the bill introduces a capacity-based cess on pan masala manufacturing machinery to fund public health and national security needs.By taxing production capacity rather than declared sales, the law aims to curb under-reporting. Manufacturers, however, argue the model is inflexible, especially during machinery downtime, while opposition parties flagged concerns over Centre–state fiscal balance.

Repealing and Amending Bill, 2025

Marketed as a clean-up exercise, the bill repeals 71 obsolete laws, some dating back to the 19th century, including the Indian Tramways Act (1886).While the government said this would simplify compliance, the opposition criticised the bulk repeal approach, arguing that several laws enacted as recently as the last decade were removed without adequate scrutiny.

Labour Codes

Though passed earlier, the four labour codes entered operational phase in November 2025, consolidating 29 laws into four frameworks covering wages, social security, industrial relations and workplace safety.The new 50% basic wage rule strengthens retirement benefits but reduces immediate take-home pay. Trade unions argue the codes tilt the balance in favour of employers, while the government maintains they modernise labour regulation for a changing economy.

Spoken but not concluded

Several issues dominated debate without resolution.

Electoral roll revision (SIR)

The opposition accused the Special Intensive Revision exercise in nine states and three UTs of selectively deleting voters. A 10-hour debate ended in deadlock, with no changes to election procedures.

Manipur crisis

Despite repeated demands, Parliament saw no dedicated discussion on Manipur, where President’s Rule remains in place. Political blame-trading replaced consensus on a peace roadmap.

Air pollution

Acknowledged as a national health emergency, air quality was debated but left without legislative follow-through or a national clean air framework.As Parliament heads into the Budget Session of 2026, the legislative record of the past year offers both momentum and caution. Several reforms have been passed, others deferred, and many now enter the more difficult phase of implementation. Whether the coming session delivers clarity, consensus and course correction — or repeats the disruptions of 2025 — remains to be seen. Go to Source