Plov is everywhere in Uzbekistan. A medley of rice, carrots, chickpeas, meat and the tart but sweet pop of berries, it’s hearty sustenance and cultural glue. There’s a love angle too: legend has it that Ibn Sina, the Bukhara-born father of modern medicine, invented plov as a recipe to heal the broken heart of a lovelorn prince who could not marry the daughter of an artisan. That myth, with its mix of nourishment and repair, has become the starting point for the inaugural Bukhara Biennal. Aptly titled ‘Recipes of Broken Hearts’, it brings food, craft, and art together in search of new ways of healing.At the opening walkthrough, curator Diana Campbell explains: “I think we’re living in very heartbreaking times. And while a biennial cannot heal the many, many heartbreaks of the world, maybe it can help heal certain problems in the art system which are, I think, unfair — for instance, the distinctions made between makers versus ideators. So, all the projects in the biennal are collaborative.”With 70 site-specific projects and over 200 artists and artisans from 39 countries participating, the scale is ambitious. From Mumbai to Bukhara, Shakuntala Kulkarni bridged distances through plane rides, Zoom calls, and thumbs-up signs. She worked with musicians from the Bukhara Philharmonic, yurt masters from Karakalpakstan, and cane-weaving artisans from Assam. “Initially, there were communication issues but when we practised together, the piece evolved naturally,” says Kulkarni, whose three works are displayed in a caravanserai in the newly restored city centre. In one, a shackled tandoor—used for cooking in both countries—becomes a metaphor for the female body; viewers climb inside to watch a film about shedding fear and learning to trust. In another, a woman’s hands struggle to open a door, her gritty determination almost palpable. “The pieces resonated with women here because they too have experienced domestic violence.”Collaboration also anchors ‘Salt Carried by the Wind’, a kitchen-pavilion co-created by artist Subodh Gupta—who has taken everyday objects like bartans global —and Uzbek ceramicist Baxtiyor Nazirov. Its exterior is clad in humble Soviet-era pots, its interior lined with colourful tourist plates. Part dining room, part performance stage, it turned cooking into live art as Gupta served an Indian-inspired menu on Nazirov’s handcrafted dishes. Alongside chuskis and bhelpuris are somsa (samosas) and plov (pulao), a nod to centuries of Silk Road exchanges. “Both India and Uzbekistan are tied together by the Silk Road,” Gupta says. “This work reminds us of how flavours and stories connect us.”

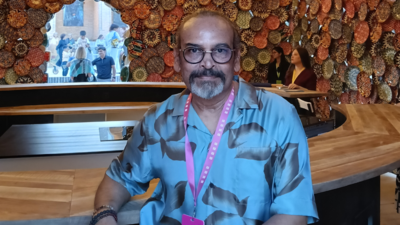

Gayane Umerova, chairperson of Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, wants to put the former Soviet republic on the global culture mapWhile food is of course a delicious connection, there is also the art of ikat weaving. Chennai-born and US-based architect Suchi Reddy created an ikat-inspired canopy with Uzbek weaver Malika Berdiyarova. Installed in the historic Gavkushon madrasa, its play of shadows offers respite from the heat and blends seamlessly with Bukhara’s two-toned indigo and sandstone backdrop.That spirit of connection continues in the monumental two-part tapestry of Khadim Ali, who is represented by Latitude 28, a Delhi gallery that showcases emerging South Asian artists. Ali, from a Hazara family forced to flee Afghanistan, worked with Uzbek embroiderer Sanjar Nazarov and Afghan artisans who remain anonymous for safety. Inspired by Persian epic poetry that links Bukhara to his own heritage, the work retells the story of the Simurgh, the mythical bird that protects people from destruction and heartbreak.The biennal also shows how art collapses boundaries: selfie-takers outside Gupta’s pavilion, a little boy sneaking a lick at a rock-sugar installation, and proud locals sharing kilos of plov and kebabs with artists, gallerists, and curators from across the globe. The biennial doesn’t just blur the line between art and craft, global and local, it also bridges the distance between the art world and ordinary people.Bukhara’s old town, with its minarets, mosques, and madrasas, provides a stunning backdrop. But it also comes with heat and dust—conditions most museums would find unthinkable. As Campbell noted, “All of these works are made in the places where people in Uzbekistan actually live—often without air-conditioning, in dusty environments. That doesn’t mean art can’t exist here; in fact, it’s a quiet critique of the over-museified system that insists artworks must always be kept at the same sterile temperature and conditions everywhere. Of course, I hope museums collect and protect these pieces for the long term. But here, the artists understand that the sun, the dust, and the wind are collaborators in the work.”In the process, the city itself becomes a living museum—its restored sites not just tourist attractions but stages where art and history mingle. Uzbekistan’s cultural ambitions stretch beyond Bukhara. Gayane Umerova, chairperson of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation, has a wider vision of positioning the country as a creative hub. A new national museum is slated to open in 2028, while in the capital, Tashkent, cultural spaces are being revitalized. A restored tram depot, for example, will host artist residencies and workshops. “We’re not approaching it with nostalgia, we see it as part of the future,” says Umerova, who has travelled several times to India and been struck by its efforts to elevate craft. Go to Source