Reha Kansara and Ghoncheh HabibiazadBBC News and BBC Persian

Getty Images

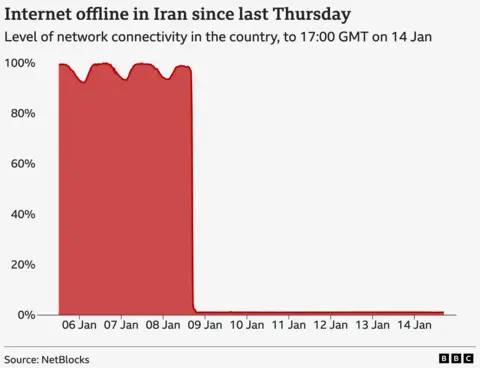

Getty ImagesStarlink has reportedly waived monthly subscription payments for users inside Iran after its government shut down the internet last Thursday – cutting off millions of people from their families, livelihoods and access to information, during a deadly crackdown on protests.

The satellite technology has become a vital communications lifeline for some of those in the country trying to tell the outside world what has been happening on the ground in recent days.

Two people in Iran told BBC Persian their device was running on Tuesday night even though they had not been keeping up with subscription payments. The director of an organisation that helps Iranians get online also told BBC Persian that Starlink had been made free.

The satellite technology, which belongs to Elon Musk’s SpaceX company, provides internet to tens of thousands of people in Iran, despite the fact it is illegal there. Since the internet was shut down, it has become one of the last, if not the last, remaining channels for Iranians to communicate with the outside world.

The BBC has approached SpaceX to confirm it has waived the fee, but they are yet to respond.

Using the service in Iran carries a punishment of up to two years in prison and authorities have reportedly been searching for Starlink dishes to stop people from connecting to the internet.

“They’re going onto rooftops and checking the surrounding buildings,” says Parsa – not his real name – who spoke to BBC Persian using a Starlink connection.

“What people need to know is that the government is searching areas where a lot of footage has come out, so they need to be even more cautious,” he says.

The device operates like a mobile phone mast in space, using a constellation of satellites to communicate with small dishes on the ground with a built-in WiFi router.

But the device is costly and beyond the means of many in Iran – so making it free may lead to its wider use.

Speaking to Al Jazeera TV on Monday, Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi said the internet had been cut off “after we confronted terrorist operations and realised orders were coming from outside the country”.

Iran’s Fars news agency, which is affiliated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), claimed internet restrictions were imposed to stop foreign social media platforms such as WhatsApp and Instagram being used “to organise violence and unrest.”

Human rights groups have condemned the blanket blackout as an abuse of power and a spokesperson for the UN’s Human rights office told the BBC the shutdown “impacts the works of those documenting human rights violations.”

So far, one human rights group has confirmed the killing of more than 2,400 protesters during the unrest, as well as almost 150 people affiliated with security forces, although these numbers are believed to be much higher.

It is difficult to gauge the true scale of bloodshed because, like other international news organisations, the BBC is not able to report from inside the country.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe internet shutdown has also made it hard to gather and verify evidence of what is happening on the ground.

“I think a lot of people are connected, but only a very small number are taking the risk of sending information out,” explains Parsa.

According to human rights organisation Witness, at least 50,000 people are using Starlink to access the internet.

Mahsa Alimardani, who works as its associate director for technology, threats and opportunities, says the Iranian authorities have tried “aggressively jamming” Starlink to stop people accessing the internet but it has not been successful. “That’s why they are resorting to physical confiscations,” she adds.

But those who are taking the risk are going to great lengths. One man who spoke to BBC Persian said he travelled almost 1,000km (620 miles) to a border area so he could use mobile networks of neighbouring countries to send video he recorded.

The scene he witnessed – of a huge number of bodies lying on the ground at a forensic medical centre in Tehran – was so distressing that he felt compelled to share it, he told the BBC.

The Iranian government has a long track record of spying on its citizens, including digitally, to tighten its grip on society.

Phishing techniques have reportedly been used to hack phones and access people’s data and Iran’s access to the internet is largely restricted to a domestic service that mimics a private intranet.

Access to Western social media platforms such as Instagram, WhatsApp and Telegram is blocked, meaning Iranians have to use virtual private networks (VPNs) in order to access them.

But despite this, Instagram is one of the most popular platforms in Iran, with an estimated 50 million users.

BBC News

BBC NewsThough some news is being shared online, experts say the Iranian government aims to control the narrative by limiting what information gets out.

Ana Diamond, research associate at the Oxford Disinformation and Extremism Lab, says the government is weaponising information by carefully curating it.

“Such material is designed less to inform than to condition; to almost normalise casualties, especially as the Iranian government calls them rioters, eroding collective resistance, and preparing the public – both inside and outside of Iran – for escalations of violence that may be yet to come if the protests continue,” Diamond says.

Despite the dangers, Starlink has become indispensable for many Iranians communicating what is happening inside the country to the rest of the world.

“I’d rather not think about it [getting caught]. It can be very frightening,” Parsa says.

On Tuesday, Iranian intelligence forces said they had seized a large consignment of Starlink kits allegedly intended for “espionage and sabotage operations” inside the country.

However, BBC Persian has confirmed through multiple sources in Iran that the kits are used by many people wanting to communicate without censorship.

Parsa cautions that getting caught using the device is not the only danger.

If Iranians want to send videos that are shared or intercepted online, he says, “they need to understand that if they record them from home or from the place where the device is kept, their risk increases, and the government can identify the location”.

Additional reporting by Hadi Nili, BBC Tech correspondent