Jeremy BowenInternational Editor

BBC

BBCA year ago, the war that President Bashar al-Assad seemed to have won was turned upside down.

A rebel force had broken out of Idlib, a Syrian province on the border with Turkey, and was storming towards Damascus. It was led by a man known as Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, and his militia group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

Jolani was a nom-de-guerre, reflecting his family’s roots in the Golan Heights, Syria’s southern highlands, annexed by Israel after it was occupied in 1967. His real name is Ahmed al-Sharaa.

One year later, he is interim president, and Bashar al-Assad is in a gilded exile in Russia.

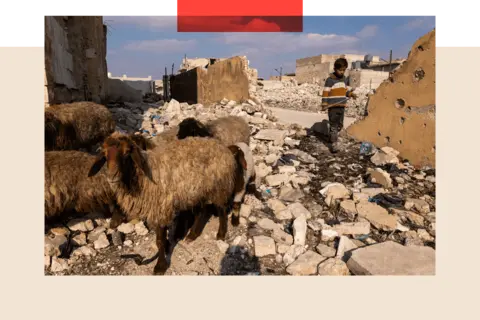

Syria is still in ruins. In every city and village I have visited this last 10 days, people were living in skeletal buildings gutted by war. But for all the new Syria’s problems, it feels much lighter without the crushing, cruel weight of the Assads.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSharaa has found the going easier abroad than at home. He has won the argument with Saudi Arabia and the West that he is Syria’s best chance of a stable future.

In May, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia arranged a brief meeting between al-Sharaa and US President Donald Trump. Afterwards, Trump called him a “young attractive tough guy”.

At home, Syrians know his weaknesses and the problems Syria faces better than foreigners. Sharaa’s writ does not run in the north-east, where the Kurds are in control, or parts of the south where Syrian Druze, another minority sect, want a separate state backed by their Israeli allies.

On the coast Alawites – Assad’s sect – fear a repeat of the massacres they suffered in March.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesA year ago, the new masters of Damascus, like most of the armed rebels in Syria, were Sunni Islamists. Sharaa, their leader, had a long history fighting for al-Qaeda in Iraq, where he had been imprisoned by the Americans, and then was a senior commander with the group that became Islamic State.

Later, as he built his power base in Syria, he broke with and fought both IS and al-Qaeda.

People who had travelled to Idlib to see him said that he had developed a much more pragmatic set of beliefs, better suited to governing Syria, with its spectrum of religious sects. Sunnis are the majority. As well as Kurds and Druze, there are Christians, many of whom find it hard to forget Sharaa’s jihadist past.

Image of a man who outgrew his jihadist roots

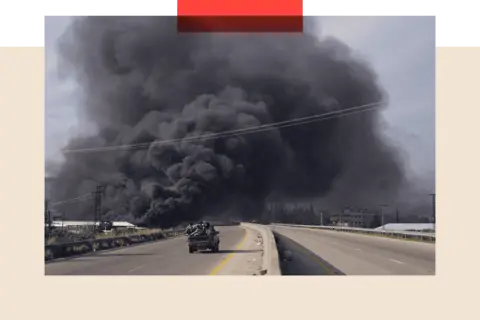

In the first week of December last year, it was hard to believe that the HTS offensive was moving so fast. It took them three days to capture Aleppo, Syria’s northern powerhouse.

Compare that with the tortured years between 2012 and 2016, when the regime’s army and rebel militias had fought for control of the city: that had ended in victory for Assad after Russia’s president Vladimir Putin deployed his air force and artillery to add decisive firepower to the regime’s ruthless tactics.

When I visited the former rebel strongholds in eastern Aleppo a few weeks after they had fallen to the regime, large areas were devastated by Russian bombing. Some streets were blocked by rubble that went up to first-floor balconies.

But by the end of 2024, across the country, government troops had melted away. Both reluctant conscripts and regime loyalists were no longer prepared to fight and die for a corrupt and cruel regime that repaid them with poverty and oppression.

AFP via Getty Images

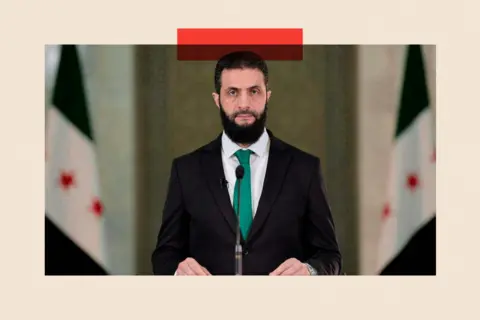

AFP via Getty ImagesA few days after Assad fled with his family to Russia, I interviewed Syria’s victorious new leader in the presidential palace.

It perches high on a crag overlooking Damascus, designed as an ever-visible reminder for the city’s citizens of the all-seeing power of the Assads. By then Jolani had discarded his name, along with his combat fatigues.

Sharaa sat down in the chilly halls of the unheated palace wearing a smart jacket, pressed trousers and shiny black shoes. He told me that the country was exhausted by war and was not a threat to its neighbours or to the West, insisting that they would govern for all Syrians. It was a message that many Syrians and foreign governments wanted to hear.

Israel dismissed it, however. And jihadist hardliners branded Sharaa as a traitor, selling out his religion and his own history.

I had packed in a hurry to report on a war, never expecting the regime to crumble so fast. My formal attire was back at home in London. After the interview one of his aides complained that I should have worn a suit to interview a national leader.

His grumble was about more than my sartorial choices. It was the continuation of a long campaign that had started years earlier as Sharaa built up his power in Idlib. The campaign was designed to present him as a man who had outgrown his jihadist roots to become a worthy leader of all Syria, a leader the rest of the world should take seriously and treat with respect.

A weakened IS in Syria

Sharaa took power amid huge uncertainty about what he might do, and what might be done to him by his enemies. Among them were dark fears that the jihadist extremists of Islamic State, still existing in sleeper cells, could try to kill him, or cause chaos with mass casualty attacks in Damascus.

Jihadists rage on social media about Sharaa’s charm offensive in the west. After he agreed to join the US-led coalition against Islamic State, prominent voices online branded him an apostate, a Muslim who had turned on his own religion. Extremists could take that as a licence to kill.

The reality is that IS in Syria is weak. Its attacks this year have been mostly against Kurdish-led forces in the north-east.

That has changed in the last few weeks, leading up to the anniversary of the fall of the Assad regime.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs security forces have raided IS cells, the jihadists have killed three soldiers and two former Assad operatives in cities controlled by the government, according to data collected by Charles Lister, a leading commentator on Syria, and published in the newsletter Syria Weekly. IS social media channels monitored by the BBC continue to tell Syrian Sunnis that Sharaa has betrayed them.

Without producing any proof, they have posted claims that he has been an agent of the US and UK, working to undermine the jihadist project.

Winning over Trump and the west

Sharaa’s overtures to the west have been remarkably successful.

Within two weeks of taking power in Syria, he received a delegation of senior American diplomats. Immediately, the Americans scrapped the $10 million bounty the they had put on his arrest.

Since then, sanctions imposed on Assad’s Syria have been steadily reduced. The most swingeing, the Caesar Act, has been suspended and could be repealed by the US Congress in the new year.

A major milestone came in November when Sharaa became the first Syrian president to visit the White House.

AP

APTrump’s welcome in the Oval Office was relaxed. He sprayed Sharaa with Trump-branded cologne, before presenting him with his own supply to take home for his wife, jokingly asking him how many he has. “One,” Sharaa answered, as he blinked away clouds of fragrance.

Away from the larking around for the cameras, Saudi Arabia as well as western governments see Sharaa as the best bet – the only one – to stabilise a country that sits at the heart of the Middle East.

If Syria slipped back into civil war, there would be zero chance of reducing the violent turbulence in the region.

One senior western diplomat told me that the conditions for civil war still exist. That is because of the lasting scars of half a century of dictatorship and 14 years of a war that started as an uprising against the Assads’ oppressive rule and turned into an increasingly sectarian fight.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesSharaa is a Sunni Muslim, Syria’s largest religious group. His government does not control the whole country. In the last year he has not been able to persuade, or force, Kurds in the north-east and Druze in the south to accept the authority of Damascus. On the coast, the Alawite community is nervous and restive.

The Alawites are a sect that originated in Shia Islam, with their heartland on Syria’s Mediterranean coast. The Assads are Alawites.

The founder of the regime, Bashar’s father Hafez al-Assad built his power on the Alawite minority, around 10% of the population. Just the sound of the Alawite accent, especially coming from a man in uniform – or worse, a leather-jacketed operative from one of the regime’s intelligence agencies – used to make other Syrians nervous.

Syria will not recover if sectarian killing continues. Stopping more serious outbreaks of violence in the next 12 months is the government’s most serious challenge.

The slow pace of justice

Just before the anniversary of Assad’s fall, the UN human rights office (OHCHR) expressed serious concern about the slow pace of justice. A spokesman said that “While the interim authorities have taken encouraging steps towards addressing past violations, these steps are only the beginning of what needs to be done.”

Some Syrians have taken matters into their own hands, along, at times, with government forces. The OHCHR said that the hundreds have been killed over the past year “by the security forces and affiliated groups, elements associated with the former government, local armed groups and unidentified armed individuals”.

They added: “Other reported violations and abuses include sexual violence, arbitrary detentions, destruction of homes, forced evictions, and restrictions on freedoms of expression and peaceful assembly.”

Alawite, Druze, Christian and Bedouin communities were mainly affected by the violence, the OHCHR said, which has been fed by rising hate speech both on- and offline.

Anadolu via Getty Images

Anadolu via Getty ImagesA big risk for 2026 is a repeat of last March’s sectarian violence in Alawite areas.

In the security vacuum that followed the fall of the Assad regime, the new government attempted to stamp its authority on the Syrian coast with a series of arrests. An investigation by OCHCR found that “pro-former government fighters responded by capturing, killing, and injuring hundreds of interim government forces”.

Damascus responded harshly and lost control of militant armed factions that carried a systematic series of deadly attacks on Alawites.

The UN found that some 1,400 people, predominantly civilians, were reported killed in the ensuing massacres. The vast majority were adult men, but victims included approximately 100 women, the elderly and the disabled, as well as children.

The Sharaa government cooperated with the UN investigation. Some of its forces managed to rescue Alawites and it has put some of the ringleaders of the massacres on trial.

Reuters

ReutersThe UN Syria Commission of Inquiry confirmed it had found no evidence the authorities had ordered the attacks. But the concern then and for the future was that the Damascus government could not control armed Sunni groups that had supposedly joined its security forces.

In July in the southern province of Sweida, serious violence between Druze and Bedouin communities shook the Sharaa administration to its roots. The Druze religion developed out of Islam around a thousand years ago, and its followers, who some Muslims believe are heretics, amount to around 3% of Syria’s population.

When government forces entered Sweida, supposedly to restore order, they ended up fighting Druze militias. Israel, which has its own Druze community that is fiercely loyal to the Jewish state, intervened. Its airstrikes included the near destruction of the ministry of defence in Damascus.

It took a rapid American intervention to force a ceasefire that stopped a spiral down into much worse violence. Tens of thousands of people were driven from their homes and remain displaced.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Israel question

It is still not clear whether Sharaa and his interim government are strong enough to survive another crisis as serious as that. Israel remains a looming and dangerous presence to Syrians.

After the fall of Assad, the Israelis launched a series of major air strikes to destroy what was left of the old regime’s military capacity. The IDF advanced out of the occupied Golan Heights to take control of more Syrian territory, which it still holds.

Officials stressed at the time that Israel was acting in its own national security interests. They said the aim was to stop weapons that the regime held falling into the wrong hands or being turned in its direction.

Attempts by the US to broker a security agreement between Israel and Syria have stalled in the last two months or so.

Syria wants to return to an agreement originally negotiated by Henry Kissinger when he was US Secretary of State in 1974. Netanyahu wants Israel to stay in the land it seized and has demanded that Syria demilitarises a large area south of Damascus.

In the last month Israel has intensified its ground incursions into Syria. Syria Weekly, which collects data on violence, calculates that there were more than twice as many as the monthly average for the rest of the year.

We visited the border village of Beit Jinn, which was raided by IDF troops on 28 November. The IDF said they were arresting Sunni militants who were planning attacks.

Local men fought back, wounding six Israelis as the raiding party was forced into a hurried retreat, abandoning a military vehicle that they later destroyed with an airstrike. The Israelis killed at least 13 local people and wounded dozens, state media reported.

It was a sign of how hard it will be to broker a security deal between Syria and Israel. The Damascus government called it a war crime. Calls for retaliation intensified.

Dia Images via Getty Images

Dia Images via Getty ImagesIn Washington, Trump was clearly worried by the raid. He posted on his Truth Social platform that he was “very satisfied” with Sharaa’s efforts at stabilising Syria.

He warned that it was “very important that Israel maintain a strong and true dialogue with Syria, and that nothing takes place that will interfere with Syria’s evolution into a prosperous state”.

In Beit Jinn I met Khalil Abu Daher on his way back from hospital, his arm in plaster after surgery for a bullet wound. He invited me to his home, which is close to where the Israelis were exchanging fire with village men.

Khalil told me he was here with his family when the Israelis entered the village at 03:30 am. They tried to find a safe place.

“I was in my house with my children. We went from one room to another. They shot at my two daughters. One was hit, and the other died instantly. When I picked her up, I was shot in the hand.”

The dead girl was 17-year-old Hiba Abu Daher, who was shot in the stomach. They sheltered, Khalil said, alongside Hiba’s dead body for two hours before they were rescued and taken to hospital.

When I visited, Khalil’s nine-year-old daughter was lying on a blanket on the sofa, recovering from surgery to take a bullet out of her hip.

The girls’ mother, Umm Mohammad, sat with the women of the family, desperately worried about the future.

“We want peace of mind,” she told me. “We want to live in our homes, and we want a clinic and medical staff because we don’t have one.

“We also want a doctor because there isn’t one in Beit Jinn, nor is there a pharmacy. We want security.”

‘We go to sleep and wake up afraid’

A year after the end of Assad’s rule, Syria’s new rulers have scored some important achievements.

They are still in power, which was not guaranteed when they took Damascus. President Trump has become Sharaa’s most important backer. Sanctions are being lifted. The economy is showing signs of life and business deals are being done, including modernising oil and gas installations and privatising the airports in Damascus and Aleppo.

But deals that are in the pipeline have not yet changed the lives of most Syrians. The government has no rebuilding fund. Reconstruction is up to individuals. Sectarian tensions are unresolved and could ignite again. The US-mediated dialogue with Israel has stalled.

NurPhoto via Getty Images

NurPhoto via Getty ImagesBenjamin Netanyahu insists that Damascus might demilitarise a large area of southern Syria and shows no signs of ordering the IDF to pull back. Both points amount to a major violation of Syrian sovereignty. The Beit Jinn raid makes it harder for Damascus to offer concessions.

Government in Damascus is centred on Sharaa himself, assisted by the foreign minister Asaad al-Shaibani and a few trusted associates. No serious attempt seems to be happening to create an accountable framework of government.

Syria without the Assad family is a better place. But Umm Mohammad summed up the feelings of far too many Syrians.

“The future is difficult. We have nothing, not even schools. Our children are living in hell here. There is no safety for them. How will we live?

“We want safety. We go to sleep and wake up afraid.”

Top picture credits: AFP via Getty Images and Anadolu via Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. You can now sign up for notifications that will alert you whenever an InDepth story is published – click here to find out how