Will GrantBBC’s Mexico, Central America and Cuba correspondent, Colombia

EPA/Shutterstock

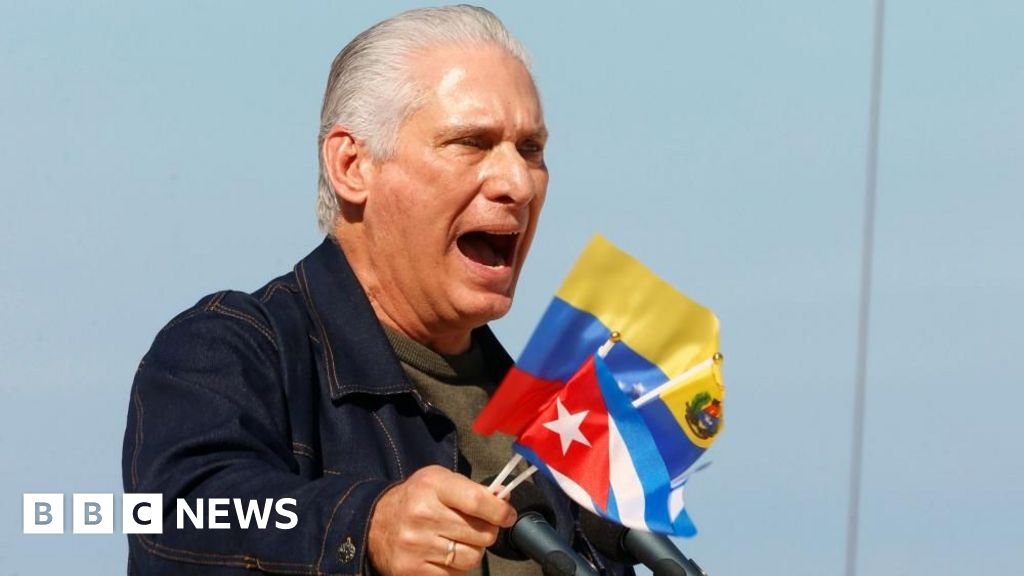

EPA/ShutterstockAfter Venezuela, there is no nation in the Americas more affected by the events in Caracas than Cuba.

The two nations have shared a political vision of state-led socialism since a fresh-faced Venezuelan presidential candidate, Hugo Chávez, met the aged leader of the Cuban Revolution, Fidel Castro, on the tarmac at Havana airport in 1999.

For years, their mutual ties only deepened, as Venezuelan crude oil flowed to the communist-run island in exchange for Cuban doctors and medics travelling in the other direction.

After the deaths of the two men, it was Nicolás Maduro – trained and instructed in Cuba – who became Chávez’s handpicked successor, chosen partly because he was acceptable to the Castro brothers. He represented continuity for the Cuban revolution as much as the Venezuelan one.

Now he, too, is gone from the seat of power in Caracas, forcibly removed by the US’s elite Delta Force team. The prospects for Cuba in his absence are bleak.

For now, the Cuban government has robustly denounced the attack as illegal and declared two days of national mourning for 32 Cuban nationals killed in the US military operation.

Their deaths revealed a key fact long-known about Cuban influence over the Venezuelan presidency and military: Maduro’s security detail was almost entirely made up of Cuban bodyguards. Cuban nationals are in place in numerous positions in Venezuela’s intelligence services and military too.

Cuba had long denied having active soldiers or security agents inside Venezuela, but freed political prisoners have often claimed they were interrogated by men with Cuban accents while in custody.

Furthermore, despite endless public proclamations of solidarity between the two nations, in truth the Cuban influence behind the scenes of the Venezuelan state is believed to have driven a wedge between ministers most closely aligned with Havana and those who feel that the relationship first established by Chávez and Castro has become fundamentally unbalanced.

In essence, that faction considers that these days Venezuela gets little in return for its oil.

Venezuela is believed to send around 35,000 barrels of oil a day to Cuba – none of the island’s other main energy partners, Russia and Mexico, even come close.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Trump administration’s tactic of confiscating sanctioned Venezuelan oil tankers has already begun to worsen the fuel and electricity crisis in Cuba and has the potential to become very acute, very quickly.

At best, the future looks increasingly complex for the beleaguered Caribbean island without Maduro at the helm in Caracas. Cuba was already in the grip of its worst economic crisis since the Cold War.

There have been rolling blackouts from end to end of the island for months. And the impact on ordinary Cubans has been taxing in the extreme: weeks without reliable electricity, food rotting in fridges, fans and air-conditioning not running, mosquitoes swarming in the heat and the fester of uncollected rubbish.

The island has experienced a widespread outbreak of mosquito-borne diseases in recent weeks with huge numbers of people affected by dengue fever and chikungunya. Cuba’s healthcare system, once the jewel in the revolution’s crown, has struggled to cope.

It is not a pretty picture. Yet it is the daily reality for most Cubans.

The idea that the flow of Venezuelan oil to Cuba could be turned off by Delcy Rodríguez fills Cubans with dread, especially if she looks to placate the Trump administration following the US raid against her predecessor and stave off the spectre of more violence.

EPA/Shutterstock

EPA/ShutterstockPresident Trump insists Washington is calling the shots in Venezuela now.

While those comments were walked back – to an extent – by his Secretary of State Marco Rubio, there is no doubt that the Trump administration now expects nothing less than total compliance from Rodríguez as acting president.

There would be further, potentially worse consequences, Trump threatened, if she “doesn’t behave”, as he put it.

Such language – not to mention the US operation in Venezuela itself – has shocked and angered Washington’s critics, who say the White House is guilty of the worst form of US imperialism and interventionism seen in Latin America since the Cold War.

The removal of Maduro from power amounted to kidnapping, those critics argue, and the case against him must be thrown out at his eventual trial in New York.

Unsurprisingly, Trump appears unfazed by such arguments, warning he might even carry it out again against the president of Colombia if need be.

He has dubbed the worrying new circumstances in Latin America the “Donroe Doctrine”, in a nod to the Monroe Doctrine – a 19th Century colonialist foreign policy principle which warned European powers against meddling in the US sphere of influence in the Western hemisphere.

In other words, Latin America is the US’s “backyard”, and Washington has the unalienable right to determine what happens there. Rubio used that very term – backyard – about the region as he justified the actions against Venezuela on US Sunday talk shows.

He also remains key to what comes next for Cuba. The US economic embargo has been in place for more than six decades and failed to remove the Castro brothers or their political project from power.

Rubio – a Cuban American former Florida senator and son of Cuban exiles – would like nothing more than to be the man, or the man behind the man, who brought an end to 60 years of communist rule in his parents’ homeland.

He sees the strategy of removing Maduro and laying down stark conditions to a more compliant Rodríguez government in Caracas as the key to achieving that self-professed goal in Havana.

Cuba has faced tough times in the past, and the government remains defiant in the face of this latest act of US military intervention in the region.

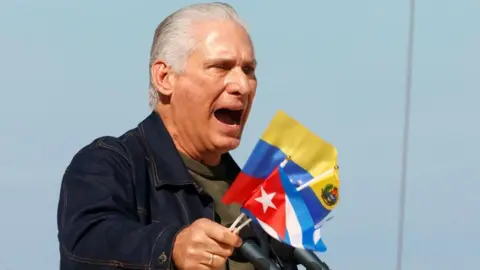

The 32 “brave Cuban combatants” who died in Venezuela would be honoured, said Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel, for “taking on the terrorists in imperial uniforms”.

“Cuba is ready to fall,” retorted Trump on Air Force One.