Steven McIntoshEntertainment reporter

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere aren’t many musicians whose sound is so distinctive and influential that the music industry invents a whole new genre to describe it.

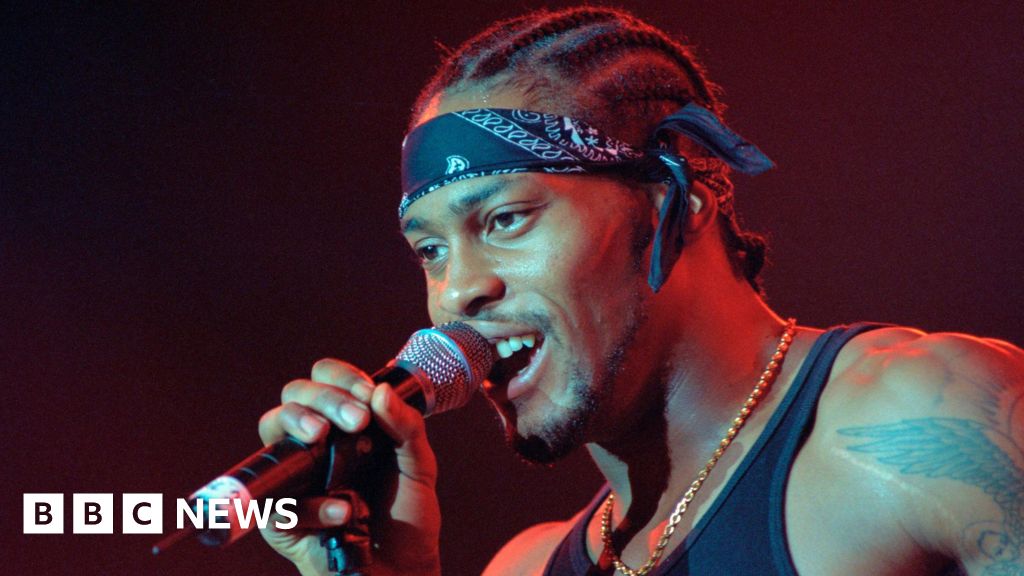

But D’Angelo, who has died at the age of 51, was seen as a trailblazer, thanks in large part to his groundbreaking debut album Brown Sugar, released in July 1995.

With its slow tempos and smooth vocals, D’Angelo’s chilled-out, late-night vibe recalled some of the legends of soul while also sounding entirely new.

R&B was already popular at the time – with TLC, Mary J Blige and Janet Jackson among the stars riding high in the charts.

But Brown Sugar’s more laid-back sound blended rhythm and blues with crisp hip-hop beats, jazz and funk, differentiating it from the more pop-skewing R&B dominating radio at the time.

The album’s sound was christened “neo-soul” – and its influence is still being felt three decades after its release.

D’Angelo’s music still crops up on streaming service playlists with titles such as “Relaxed evening vibes” and “Chilled soul classics”.

It still soundtracks dinner parties and date nights. And D’Angelo is cited as an influence not only by the artists who were his peers at the time, but by newer talents emerging today.

“He was so important, and still is,” Welsh hip-hop artist Lemfreck, who has been championed by BBC Introducing, told Radio 1’s Newsbeat.

“That neo-soul sound from the 90s and noughties is the base layer for every single layer of R&B you hear to this day.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAdmittedly, the music industry is used to coming up with buzzy names to make an unfamiliar genre more marketable.

Trip-hop was invented to help categorise Portishead and Massive Attack in the mid-90s, while the term Crunk was coined to onomatopaeically reflect the bass-heavy club sounds of Southern hip-hop.

Neo-soul was christened by D’Angelo’s own manager Kedar Massenburg, a US record producer who would later serve as president of Motown Records.

Seeing the market potential, but also just sensing a rapidly growing movement, Massenburg trademarked the term neo-classic soul, telling Billboard in 2002 that there was “the need to categorise music for consumers so they know what they’re getting”.

The term caught on, and a huge number of neo-soul artists followed in D’Angelo’s footsteps, some of them signed by Massenburg himself.

Maxwell’s Urban Hang Suite was released a year after Brown Sugar, while Erykah Badu, Jill Scott, Musiq Soulchild, India Arie and D’Angelo’s former partner Angie Stone would launch albums over the following years, a time seen as neo-soul’s golden era.

But Brown Sugar had already set the genre’s blueprint.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe album’s sales might have been slow at first, but its breakout hits Lady, Brown Sugar and Cruisin’ all made the Billboard R&B chart, and helped the record eventually reach two million in sales.

D’Angelo “emerged as a nostalgic figure in modern soul,” said Pitchfork’s Marcus J Moore. “His blend of 1970s R&B and hip-hop felt uniquely vintage and modern. He appealed to wide swaths of listeners and helped usher in a new strain of black music.”

However, as is often the case with a successful debut album, D’Angelo struggled to follow it up. He toured Brown Sugar for two years but then hit a wall while trying to work on his second record.

“The thing about writer’s block is that you want to write so badly, [but] the songs don’t come out that way,” he told Entertainment Weekly in 2008. “They come from life. So you’ve got to live to write.”

The infrequency with which he released music made D’Angelo’s albums much more of an event when they eventually appeared.

Much like Lauryn Hill, with whom he collaborated on Nothing Even Matters for her Miseducation album, D’Angelo’s towering influence was even more notable for his comparatively low level of output.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBrown Sugar’s follow-up, Voodoo, was eventually released in 2000, and hailed by critics as a triumph.

With production from Questlove and J Dilla, its sound leaned slightly more towards hip-hop than his debut, with more pulsing percussion and a collaboration with Method Man and Redman.

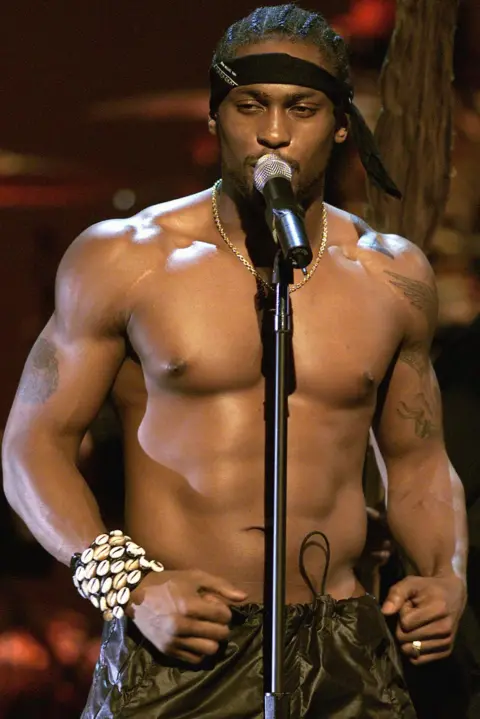

But it was the seven-minute music video for its third single Untitled (How Does It Feel) that attracted the headlines.

Filmed all in one take, the video saw D’Angelo’s face filmed close up, before the camera pulling back to reveal him standing completely naked.

D’Angelo certainly had the body to pull off the video, which went on to be nominated for three MTV VMAs, including Video of the Year.

“We made this music video for women,” said its director Paul Hunter. “The idea was, it would feel like he was one-on-one with whoever the woman was.”

The stripped-back appearance reflected the stripped-back sound of the song – the arrangement saw the instruments lower in the mix to give D’Angelo’s layered harmonies centre stage.

The frenzied reaction to Untitled pushed Voodoo to number one in the US for two weeks, and in 2001 it won the Grammy for best R&B album (the singer won four Grammy Awards from 14 nominations throughout his career).

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut D’Angelo, whose real name was Michael Eugene Archer, was uncomfortable with his new status as a sex symbol.

He already had a strained relationship with fame, which led to prolonged periods of time away from the spotlight.

The success of Voodoo and his shirtless music video led him to leave showbusiness for what would become a 14-year break before his next album.

He struggled with depression and alcohol and drug abuse, entering rehab twice, and nearly died in a 2005 car crash.

In the same year, he was given a three-year suspended sentence for cocaine possession.

A 2008 article in Spin magazine questioned where D’Angelo had disappeared to, and asked his friends and colleagues if there was any prospect of him returning to music.

D’Angelo’s former music manager, Dominique Trenier, told the magazine that both he and the singer had been disappointed by the reaction to Untitled’s music video, which had come to define D’Angelo’s career.

“I feel really guilty, because that was never the intention,” Trenier said. “I’m glad to video did what it did, but he and I were both disappointed because, to this day, in the general populace’s memory, he’s the naked dude.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut he got back on track, signing a new deal which would ultimately lead to his third and final studio album, 2014’s Black Messiah.

The vocals were unmistakably D’Angelo, but the album had a somewhat different sound. His electric guitar playing featured much more heavily on the album, giving it a more rocky sound – and earning comparisons to Funkadelic’s influential 1971 album, Maggot Brain.

The singer also experimented with psychedelia on an album which was sonically more abstract than his first two, and featured more overtly political lyrics, partly inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement which developed after the police shootings of black men.

It was, perhaps, a rejection of the neo-soul label.

“I never claimed I do neo-soul,” he said in a 2014 interview with Red Bull Music Academy. “When I first came out, I used to always say: ‘I do black music. I make black music.'”

Even Massenburg, who had invented the phrase, acknowledged: “A lot of people don’t like the term because, when you classify music, it becomes a fad, which tends to go away.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesD’Angelo may have been uncomfortable with cultural moments most closely associated with him – but he will perhaps be best remembered as an inspiration.

Paying tribute to D’Angelo on X on Wednesday, Hill said: “Thank you for charting the course and for making space during a time when no similar space really existed.

“You imaged a unity of strength and sensitivity in black manhood to a generation that only saw itself as having to be one or the other.”

Lemfreck reflects: “He was probably the first artist I heard where I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, you really can do it your own way. You really can make the thing that is right without having to appeal to the masses and still appeal to the masses’.

“The fact that he created the stuff that he did, and how he did it, is a testament to the fact that artistry always comes first.”