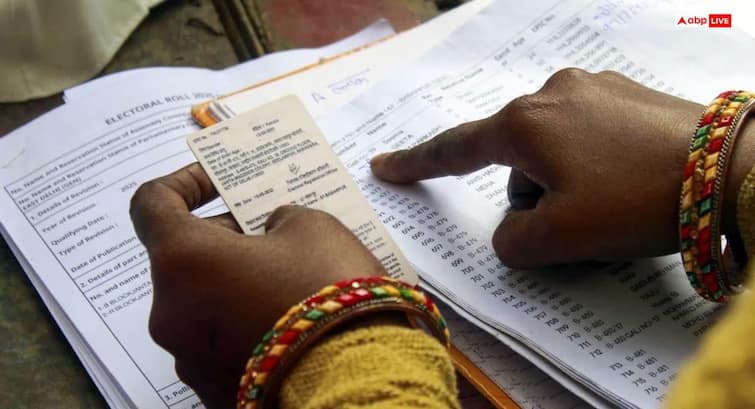

The Election Commission’s launch of the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls is on paper a much-needed housekeeping exercise, an attempt to cleanse India’s voter lists of ineligible, duplicate, or deceased names after more than two decades. By seeking verification through documents like ration cards, birth certificates, passports, and even Aadhaar (optionally), the Commission aims to bolster the integrity of the electoral process. The initiative’s second phase now spans 12 states, including politically sensitive ones such as West Bengal, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala, states heading toward crucial assembly elections in 2026.

The purpose, as the EC insists, is inclusion, not exclusion. Yet, in a country where identity and politics intersect so sharply, even a bureaucratic exercise like SIR can acquire political overtones.

At one level, the SIR deserves applause. It promises to tighten the screws on bogus voting and the persistent problem of “ghuspetiyas”, illegal immigrants, particularly from Bangladesh — a phrase that has long echoed through India’s political lexicon. Ensuring clean rolls is, after all, a constitutional necessity for free and fair elections. The Commission, empowered under Article 324, holds full authority to carry out such revisions whenever required. What remains unresolved, however, is the legal question of whether it can determine citizenship, a matter still sub judice before the Supreme Court.

But beyond the constitutional clarity lies the political haze. For the BJP, SIR dovetails neatly with its broader narrative of curbing demographic shifts through unchecked immigration, especially in border states like West Bengal and Assam. The move reinforces its rhetoric of protecting indigenous populations, potentially consolidating Hindu votes in regions where the idea of infiltration resonates deeply.

For the opposition, however, the timing of SIR’s rollout just ahead of polls in non-BJP strongholds appears far from neutral. The exercise risks being viewed as selective targeting under the garb of verification. Moreover, India’s complex federal machinery could slow down or distort implementation, especially if state administrations treat the process with political suspicion.

There is also the human cost to consider. Document-heavy scrutiny, however well-intentioned, often traps genuine citizens, particularly the poor and marginalised who lack access to formal papers. In that sense, the SIR could replay the anxieties of earlier exercises like Assam’s NRC, transforming a potentially positive reform into a political flashpoint.

Bolstering Anti-Infiltration Narrative, But Geographically Uneven Gains

SIR equips BJP with ammunition to amplify its infiltration discourse, spotlighting alleged Bangladeshi migrants inflating voter rolls in sensitive areas. From the 2024 Lok Sabha elections to the Jharkhand Assembly campaign, the BJP’s focus on the ‘ghuspetiya’ issue has consistently shaped the political narrative.

For example, in West Bengal, where porous borders have long fueled debates on illegal settlements, the revision could unearth discrepancies, validating BJP’s claims of demographic engineering by rivals.

Data from prior drives indicate thousands of dubious entries in border districts, aiding BJP’s pitch to consolidate non-Bengali Hindu and indigenous voters ahead of 2026 polls. This narrative resonates strongly here, potentially swaying marginal seats. Conversely, in Tamil Nadu, the immigrant issue lacks salience; local concerns prioritise Dravidian identity and economic woes over distant border threats, rendering SIR’s impact muted for the BJP’s fledgling presence.

Kerala presents a mixed bag, infiltration via coastal routes exists, with intelligence reports flagging networks, but BJP’s negligible footprint means any gains evaporate without organisational muscle. Thus, while SIR sharpens BJP’s rhetoric in select pockets, its persuasive power fizzles in non-core terrains, limiting nationwide electoral dividends and exposing the party’s uneven mobilisation.

Risk Of Collateral Damage To BJP’s Own Supporters

A core peril lies in SIR’s impartial scrutiny potentially pruning BJP-leaning voters, mirroring the Assam National Register of Citizens (NRC) debacle. There, the 2019 exercise excluded nearly 1.9 million residents, including substantial Hindus who failed stringent documentation tests despite generational ties.

Many Bengali Hindus, BJP’s natural allies, faced statelessness fears, prompting suicides and protests that eroded enthusiasm. BJP’s subsequent Citizenship Amendment Act sought redress for non-Muslims, but the initial backlash highlighted how rigorous verification alienates base voters lacking paperwork amid rural migrations or archival gaps.

In states like Uttar Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, where BJP dominates, SIR could similarly flag legitimate but undocumented supporters, landless labourers or informal settlers, disenfranchising them pre-poll. Without guarantees of selective leniency, this boomerang effect undermines the very purity BJP champions, fostering distrust and turnout dips among its faithful.

Meanwhile, in states like West Bengal, where the BJP relies heavily on Hindu votes, there is no guarantee that the SIR process won’t exclude voters who have traditionally supported the party.

Unusual Timing Reminds Us Of Lessons From Past

The SIR rollout’s selective phasing, encompassing West Bengal and Tamil Nadu but omitting Assam despite synchronised 2026 elections, betrays BJP’s wariness of replicable pitfalls.

Assam, a BJP bastion post-NRC, grapples with lingering re-verification appeals and citizenship limbo for excluded Hindus, making pre-poll disruption unwise. By sidelining it, the party averts reigniting grievances that could fragment its Assam coalition, including indigenous groups wary of any roll tinkering.

This omission underscores SIR’s double-edged nature: while opportunistic in opposition turf to expose rivals’ vulnerabilities, it demands restraint where BJP governs, lest it revive NRC-era narratives of Hindu exclusion. Such asymmetry fuels perceptions of instrumentalism, diluting credibility and inviting opposition counter-narratives of BJP shielding its turf while probing others.

It is also important to ask: if the issue of Bangladeshi immigration and the identification of illegal immigrants is truly a national concern, then why have Northeastern states like Mizoram, Nagaland, Manipur, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, and Tripura been excluded from the SIR list? These states, too, have long grappled with cross-border migration from Bangladesh and other neighbouring countries. This raises questions about whether the selective inclusion of West Bengal in the SIR process is politically motivated, especially given that the Bengal BJP has been vocally demanding its implementation for several months.

It is also important to note that the SIR exercise in Bihar, taking place just before the upcoming Assembly election, has proven to be particularly challenging, marked by both legal complexities and political hurdles.

Federal Hurdles Hamper EC Oversight in Opposition Domains

India’s federal fabric poses formidable execution challenges, curtailing the EC sway over state apparatuses in non-BJP realms. Though EC wields powers like curbing official transfers during SIR, it lacks command over grassroots machinery dominated by incumbents.

In West Bengal’s TMC bastions, dense cadre networks can mobilise to shield dubious entries or harass verifiers, complicating door-to-door checks. Tamil Nadu’s DMK ecosystem, with deep administrative embeds, risks similar sabotage, as seen in past poll skirmishes. Kerala’s LDF mirrors this, leveraging local bodies to contest revisions perceived as central overreach.

For poll-bound states and opposition-ruled states, these frictions amplify mismanagement odds, delayed claims and disputed deletions, eroding SIR’s sanctity and exposing EC to bias charges. BJP’s narrative gains hinge on seamless implementation, yet entrenched state powers ensure SIR remains a contested battlefield, potentially yielding incomplete purges that benefit no one fully.

(Sayantan Ghosh teaches journalism at St. Xavier’s College (Autonomous), Kolkata, and is the author of The Aam Aadmi Party: The Untold Story of a Political Uprising and Its Undoing. He is on X as @sayantan_gh.)