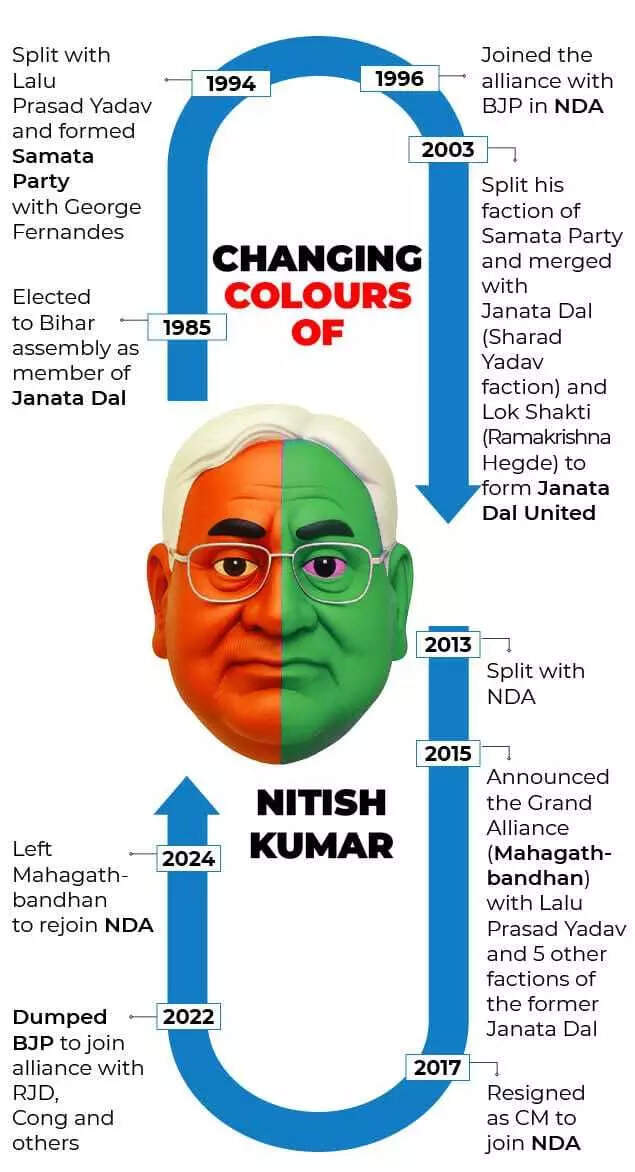

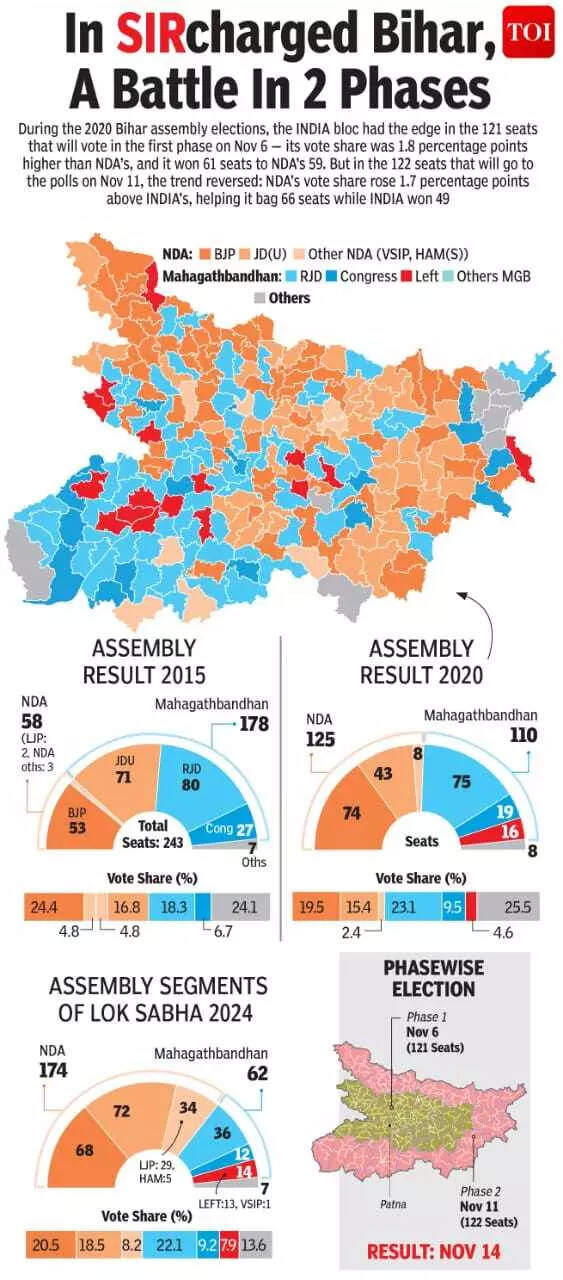

India’s political history is packed with turning points, each shaping the course of the next decade. And a very few years proved as crucial as 2013. That summer, two decisions were made within a week, which seemed to rewire Indian politics.On June 9, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) named Narendra Modi the head of its 2014 Lok Sabha election campaign committee, effectively setting him on the path to the prime minister’s office.Just seven days later, on June 16, Bihar chief minister Nitish Kumar walked out of the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA), bringing down the curtain on a 17-year partnership that had helped him rise to power. Three months later, on September 13, BJP formally declared Modi as its prime ministerial candidate.Nitish struck back, calling Modi a “divisive” leader and remarking that the BJP’s decision reflected “vinash kale vipreet buddhi” (when misfortune strikes, judgment falters). Political observers saw the break as more than a clash of personalities.Some read it as Nitish’s effort to protect his Muslim vote base in Bihar from the polarising politics associated with Modi’s BJP. Others believed it was a calculated move to keep his own prime ministerial hopes alive.

–

Cut to 2025. Nitish Kumar’s JD(U), once the dominant partner in Bihar’s NDA, will this time contest the assembly elections on equal footing with the BJP, with 101 seats each.What stands out even more is who gets those tickets. Of JD(U)’s 101 candidates this time, only four are Muslims. The sharp contrast between the Nitish of 2013 and the Nitish of 2025 begs a single question: What changed?Nitish Kumar’s evolution from the inclusionist of 2005 to the realist of 2025 is not a sudden shift. It is the outcome of two decades of political recalibration shaped by alliances, arithmetic, and survival instincts.

The JD(U) chief’s jigsaw

When Nitish came to power in 2005, his slogan “nyaya ke saath vikas” (development with justice) was aimed at building a broad coalition that could counter the Rashtriya Janata Dal’s (RJD) Muslim-Yadav base.Muslims, who make up around 17 per cent of Bihar’s population, were key to this equation.In his early years, JD(U) fielded 8–10 Muslim candidates, and several of them, like Jama Khan and Aslam Azad, won. Nitish’s outreach to Pasmanda (backwards) Muslims and welfare schemes such as scholarships, hostels, and minority commissions earned him goodwill.By 2010, JD(U) had fielded 14 Muslim candidates, the highest in its history, underscoring Nitish’s attempt to project himself as a centrist who could balance development with inclusivity even while in alliance with the BJP.The secular gambleThe split with the BJP in 2013 was presented as a stand on “secular values,” but it also had a clear political logic. Nitish sought to preserve his minority base at a time when Narendra Modi was rising at the national level and being projected as anti-minority by the opposition.In the 2015 assembly elections, JD(U) allied with the RJD and Congress, giving the Mahagathbandhan (grand alliance) a strong secular image. Although JD(U) itself fielded only 6–7 Muslim candidates (due to seat-sharing), Muslim representation across the alliance was healthy, and Nitish’s image as a moderate remained intact.

The comeback that closed doors

Nitish’s 2017 return to the BJP-led NDA marked the beginning of a slow but clear retreat from minority politics. By then, BJP dominance had grown both nationally and in Bihar, and Nitish’s political leverage had shrunk.Muslim voters, disillusioned by his flip-flops, shifted decisively toward the RJD. For JD(U), Muslim candidates now offer little electoral dividend.In the 2020 Bihar elections, JD(U) fielded just 5 Muslim candidates, down from double digits a decade earlier. By 2025, that number stands at 4, the lowest since the party’s formation.

BJP’s growing shadow

JD(U)’s declining Muslim representation also mirrors the changing power equation within the NDA. Nitish, once the “big brother” in Bihar’s alliance, now contests the same number of seats as the BJP, a symbolic indication of how much ground he has ceded.Within such a coalition, there’s limited room for independent social engineering. The BJP’s voter base is heavily majoritarian, and Nitish’s attempt to retain Muslim representation risks unsettling that core. His reduced ticket allocation is as much about coalition management as it is about electoral realism.

–

The new JD(U) constituency

Today, Nitish leans on what party insiders call his “3W” base — women, weaker castes, and welfare beneficiaries.His welfare measures for women, EBCs, and Mahadalits have replaced the old caste-plus-community model with a beneficiary-driven one. In this arithmetic, Muslim representation matters less; welfare visibility matters more.

From inclusion to isolation

Two decades ago, Nitish Kumar’s politics revolved around bringing people in. Today, it’s about holding ground. His reduced Muslim outreach does not seem to be driven by hostility, but by calculation. At the centenary celebration of the Bihar Madrasa Education Board on August 21, 2025, CM Nitish Kumar made headlines for what he didn’t do. He declined to wear the muslim headgear offered to him on stage.It was a striking image, not least because a decade earlier, Nitish had taunted Narendra Modi for the same gesture. “To run the country, you have to take everyone along,” Nitish had said then, “at times you will have to wear a topi, at times a tilak.”Back then, it was Nitish jabbing Modi on inclusion. This time, it was Modi’s old line that seemed to echo louder, the one he’d delivered in a television interview: “Muslim children should get better education and ideally, they should have the Quran in one hand and a computer in the other.”At that moment, the roles had reversed. The man who once preached symbolism now sidestepped it.Nitish Kumar’s journey captures the arc of India’s coalition-era politics itself, from the optimism of inclusion to the pragmatism of survival.His shift seems to be less about ideology and more about adaptation in an age where political space is shrinking for those who once thrived in the middle. For Bihar’s Muslims, the story of Nitish Kumar is no longer about trust lost or gained, but about a leader who adjusted to the times and, in doing so, quietly redrew the boundaries of his own politics. Go to Source