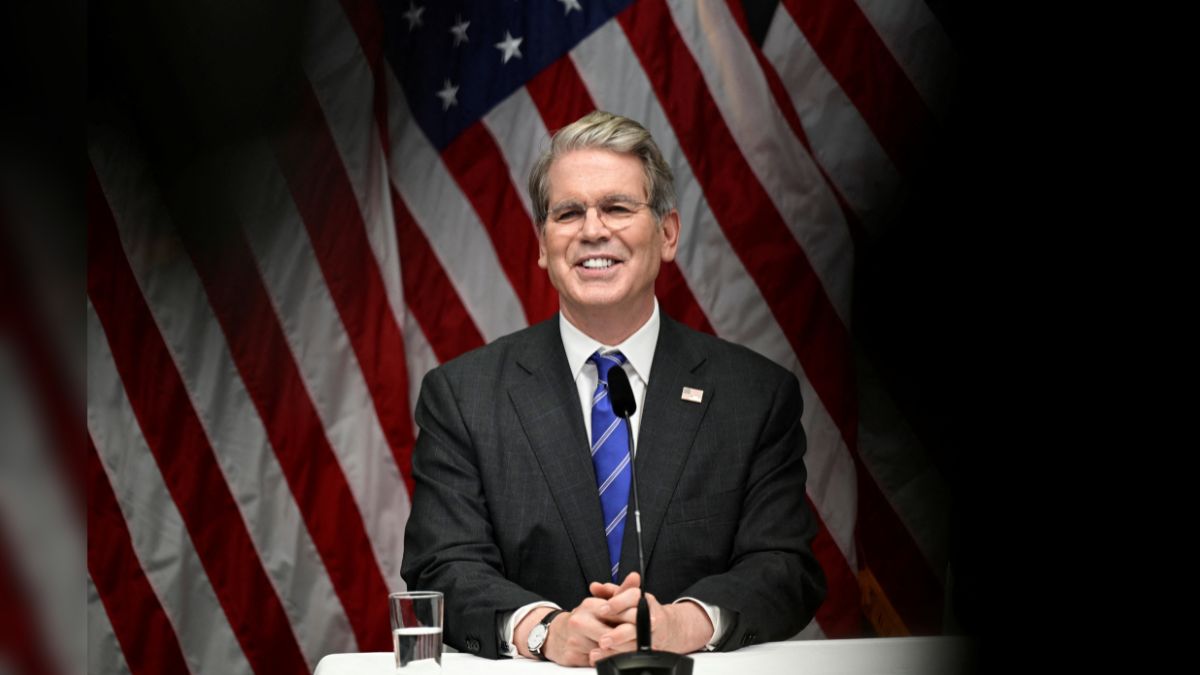

US Treasury Secretary Scot Bessent once agreed to designate two different homes as his “principal residence” at the same time.

According to mortgage records, Bloomberg reported, in 2007, Bessent’s attorney signed agreements stating that both a Georgian manor in Bedford Hills, New York and a beachfront house in Provincetown, Massachusetts, would be his main residence. The contradictory pledges mirror the kind of filings that President Donald Trump has used as grounds to try to oust Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook.

Mortgage experts have emphasised that Bessent’s case was not fraudulent arguing that lenders were fully aware of the nature of his financing. Still, the similarity between his situation and Cook’s raises questions about whether the White House has applied inconsistent standards when scrutinising mortgage agreements.

Cook’s case and Trump’s response

Cook, who was appointed to the Fed by former president Joe Biden, signed mortgage documents in 2021 for two different properties—one in Michigan and one in Atlanta. Each document required her to declare the property as a primary residence for at least a year. According to Bloomberg, however, a loan estimate from the Atlanta lender classified the condominium as a “vacation home,” suggesting the bank never expected her to occupy it full-time.

Trump seized on the filings, calling them “potentially criminal conduct” and citing them as justification to remove Cook from her post. In a letter firing her, President Trump described the pledges as evidence of “gross negligence.”

Cook has denied any wrongdoing and challenged her ouster in court. Multiple judges have blocked Trump’s bid to oust Cook from the Fed board. A federal appeals court last week ruled that she could continue working on the Fed board while her case proceeds.

How Bessent’s case played out

The Bessent mortgages were signed nearly two decades ago, on September 20, 2007, by his lawyer Charles Rich under power of attorney. Both loans came from Bank of America as part of a $21 million financing package.

In statements to Bloomberg, Rich and the bank confirmed that the Provincetown property was never intended to be a primary residence. Bank of America, in fact, issued a statement affirming its “understanding and agreement that the Bedford and Provincetown properties were secondary residences.”

Rich maintained that “there was absolutely nothing improper” about the applications, stressing that the bank had waived any requirement that the Massachusetts home be occupied as a primary residence. Bessent’s spokesperson likewise dismissed concerns, noting that he had delegated the details to counsel and that the documents were filled out properly.

One story, two stands: Trump saga

The controversy lies not so much in the filings themselves as in the political interpretation of them. Mortgage experts told Bloomberg that contradictions in occupancy clauses are not uncommon and often arise from clerical errors or missing paperwork such as a “second-home rider.”

Douglas Miller, a real estate lawyer who has testified before Congress, said that if lenders were informed about the intended use of the properties, the borrower should not be faulted. “At some point you need to rely on the fact that you made the disclosure to the lender, and if they missed a form, that’s on them,” he said.

“This whole thing is just blown out of proportion.”

Yet Trump has chosen to treat Cook’s situation as a disqualifying offence, while overlooking the similar filings made by his own Treasury secretary. Critics argue that the difference in treatment reflects political expediency rather than objective legal standards.

What Bessent said

When asked about Cook’s situation during an appearance on Fox Business in late August, Bessent did not draw attention to his own past mortgage filings. Instead, he echoed Trump’s framing of the issue, saying that “if a Fed official committed mortgage fraud, that this should be examined, and that they shouldn’t be serving as one of the nation’s leading financial regulators,” Reuters reported.

His attorney, Alex Spiro, later emphasised that nearly 20 years ago, “Mr. Bessent’s lawyers filled out paperwork properly, the bank has confirmed it was done properly, and this nonsensical article reaches the conclusion that this was all done properly.”

Wider implications of Trump’s strategy

Bessent is not the only Trump appointee with conflicting mortgage pledges. Labour Secretary Lori Chavez-DeRemer signed similar agreements in 2021 for homes in Oregon and Arizona. Her office later explained that she had intended to relocate but changed plans after deciding to run for Congress. A spokesperson dismissed the story as “a non-story invented to attack the Trump Administration”.

Meanwhile, Trump has leveraged accusations of mortgage fraud against multiple political adversaries, including New York Attorney General Letitia James and Representative Adam Schiff. Bill Pulte, the Trump appointee who heads the Federal Housing Finance Agency, has referred these cases to the Justice Department, though none have resulted in proven criminal wrongdoing.

Legal and political stakes

At the heart of the dispute is the 1913 law that created the Federal Reserve. While the statute allows presidents to remove governors “for cause,” it does not define the term. No president has ever attempted to remove a Fed governor before and the courts have never ruled on what constitutes adequate cause.

Trump’s effort to fire Cook could therefore establish a precedent that reshapes the balance between the White House and the central bank.

Mortgage experts stress that neither Cook’s nor Bessent’s filings amount to fraud, since lenders were aware of the borrowers’ true intentions. Nonetheless, Trump’s use of the issue underscores how technical mortgage language has become a political weapon. For Cook, the battle is not just over her reputation but also over the independence of the Federal Reserve.

End of Article

)