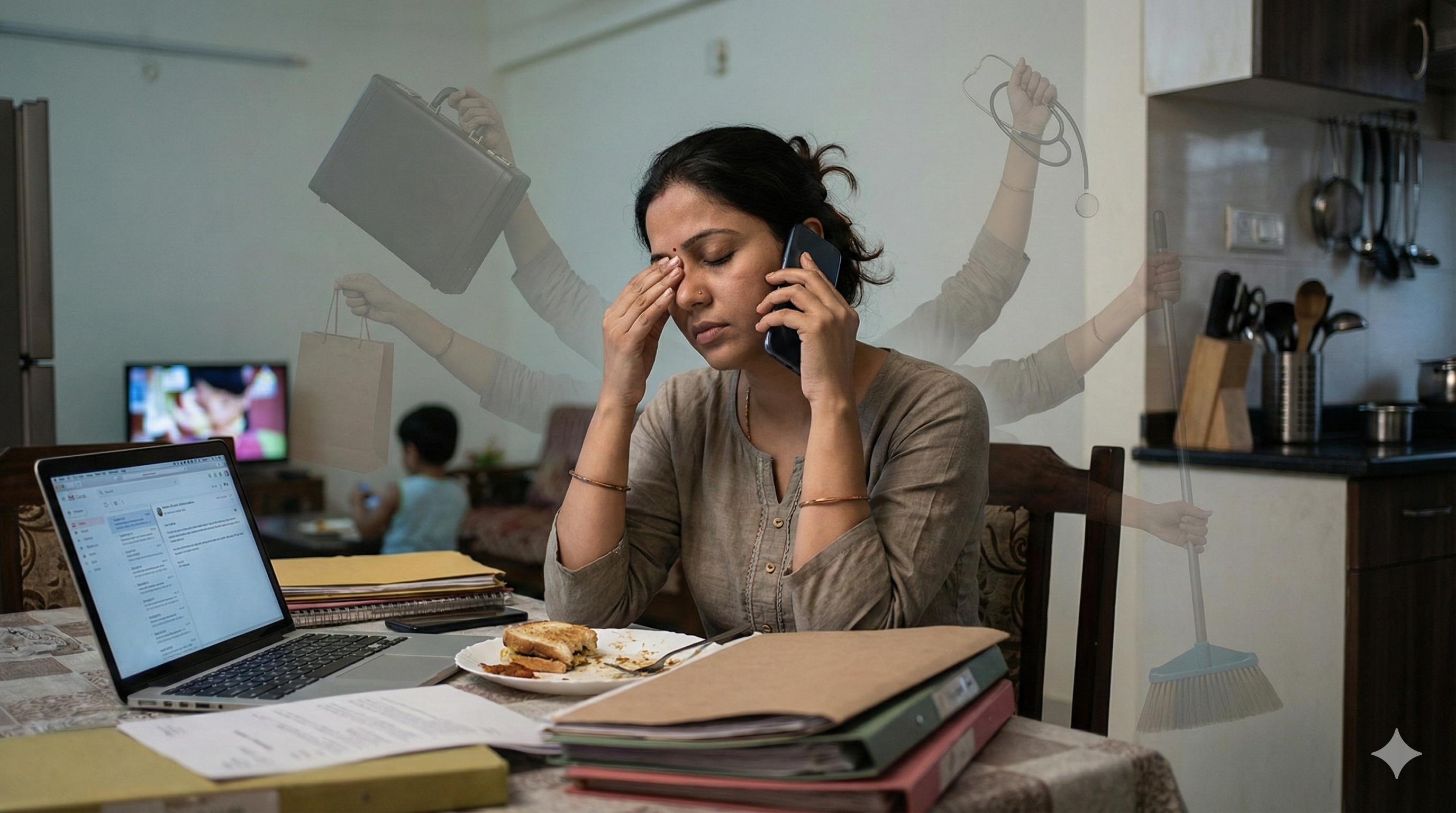

The independent woman is a familiar figure in modern India. She appears in brochures, panel discussions on TV channels and in advertising campaigns. She is praised for “managing it all” and celebrated for “having it all.” Remember the familiar image of a woman with multiple arms, each stretched thin doing everything at once?The image feels aspirational. It, however, also reveals something else: exhaustion, disguised as empowerment.

When comedian Sharon Verma once introduced herself on stage as a “weak, independent woman”, the audience laughed. The joke landed easily and stuck with many women.But beneath the laughter lies a harder truth. For many women, independence is not a victory lap. It is a daily negotiation. A weight carried quietly, often without language, sometimes without permission to put it down. “I want my child to grow up knowing that his mother is a capable woman,” says Neha Arora, 37. “Women often see themselves through the eyes of their loved ones. And when they have children, it becomes all the more important for them to be seen as strong, someone who can earn respect outside of the home.” At this stage, independence carries both aspiration and pressure. To be independent is no longer just personal fulfilment. It becomes responsibility. Strength must be visible, legible, even exemplary. Independence is no longer just lived. It is performed, observed, silently evaluated.

Calling women tired is a way of calling them unsuited for power.

Dr Medha, Psychologist

When independence was simpler

But was it always this way? Of course not.There was a time when independence felt uncomplicated. Almost exhilarating.“When I was just out of school, I thought being independent was the most courageous thing I had done. Living in a new city for further studies all by myself,” Neha recalls.That version of independence is familiar to many women. The first rented room. The first salary. The thrill of navigating unfamiliar streets alone. Independence then is discovery, tinged with fear but buoyed by possibility.

For Dr Sangita Thakur, 56, independence arrived even earlier and far more literally.“I became independent at a very early age. My parents, especially my mother, did not believe in a protective upbringing. She wanted us to grow up emotionally and financially independent, particularly because I had multiple disabilities,” she says.As a child, she commuted to school alone, visited friends on her own, and travelled without adult supervision. “My brother was nine and I was seven when we travelled alone by train from Gaya to Delhi,” she recalls. Later, as a student in Delhi, she moved through the city independently.“At that stage, independence meant freedom of movement,” she says. “Unescorted. Unquestioned.”But time, inevitably, changes the definition.“Today, my definition of strong has many more layers, like showing up for my child or managing home and work,” Neha says.What was once about self slowly becomes about others. Independence matures into endurance. Courage is no longer leaving home. It is holding everything together.

One wrong decision feels like it could ruin everything.

Jahnvi Dubey

Learning independence early and learning its cost

At 20, Jahnvi Dubey is already standing at the edge of adulthood, feeling its weight arrive faster than expected.“For me, being independent means being financially, physically, and emotionally capable of taking care of myself and my parents,” she says.“It means being able to afford the life I see in movies without feeling like a burden, and giving my parents the life they deserve.”Her idea of independence is aspirational, but it is also tethered to duty. Even before adulthood fully begins, freedom is imagined alongside responsibility.“I like that when I want something, I don’t have to ask anyone. I can just go and buy it,” Jahnvi says. “And if I see someone who needs help, I can help without seeking permission.”

But that freedom comes with urgency.“My family keeps pushing me to grow up and take responsibility,” she admits. “It feels rushed. Like one wrong decision could ruin everything.”Five years ahead of her, Vijayalaxmi Singh, 25, speaks from a slightly steadier place, but one already shaped by obligation.“For me, being an independent woman means earning a lot of money, travelling to many places around the world, and respecting everyone. Independence should come with responsibility,” she says. Her understanding did not come from slogans, but observation.“I learned what independence means by watching others. By learning from their experiences,” she says.Like Jahnvi, she feels adulthood arriving early.“Yes, family responsibilities,” she says, when asked if she already carries more than she feels ready for.When both women look at those ahead of them, admiration is inseparable from fear.Jahnvi speaks of watching her mother give up her dreams quietly, unacknowledged. “She is a fighter,” she says. “But seeing her give up her dreams just for the family showed me what true independence means. It made me want to never be that vulnerable.”Vijayalaxmi speaks of women in their thirties and forties with respect and caution. “I admire their experience,” she says. “But what scares me is how much they had to struggle to reach this stage.”Together, their voices reveal a generational truth: independence is no longer something women grow into slowly. It is expected early, demanded quickly, learned by watching other women pay its price.

The discomfort with labels

For Arpita Ghosh, 32, the phrase itself feels inadequate.“I’m honestly uncomfortable with the term ‘strong independent woman’. What does it really mean?” she asks.The label has become both compliment and containment. It compresses complexity into a catchphrase, often erasing the cost of maintaining that identity.

“To me, strength isn’t a label,” Arpita says. “It’s a moment of awareness. When you realise you are responsible for your own choices. That’s when you begin carving your own path, knowing you may falter, yet choosing to show up for yourself every day.”Dr Sangita Thakur echoes this resistance to validation-driven strength.“If I could speak to my younger self,” she says, “I would tell her this: be emotionally independent. You do not need social validation. Your life may not follow the same trajectory as your peers’, but that does not make you any less. You are complete in yourself.”For her, independence was both a choice and a necessity.”In India, especially in our time, women typically married in their twenties and moved from one protected environment to another. My journey was different. Initially, independence was simply a result of my upbringing. Over time, it became both necessary and deliberate,” she says.”I had to consider the long-term reality of remaining single. I rejected the idea of an arranged marriage, and given my progressive conditions, it was not a practical option either. Today, independence is no longer a decision. It is a habit — and an integral part of my personality,” she says.

Why strength must be performed

Psychologist Dr Medha, assistant professor at Patna Women’s College, explains why independence feels heavier for women, even when it looks similar on paper.“Financial independence dramatically increases self-efficacy for women,” she says, referencing Albert Bandura’s theory. “In societies where dependence is normalised, earning your own money reshapes how women see power, safety, and choice.”For men, financial independence is expected. For women, it is transformative.But transformation comes with scrutiny.“Women are taught that strength must be shown carefully,” Dr Medha explains. “Without making others uncomfortable. So strength becomes curated. Managed. Performed.”Dr. Sangita’s experience stands in contrast.“In my family, strength is shared rather than performed,” she says. “We are all strong individuals. We carry our load quietly, but we are deeply attuned to each other’s burdens.”

The guilt that follows work

That moral weight surfaces sharply when women step away from caregiving roles and return to the workforce.“To join the workforce again has truly been a challenge,” Neha says. “Guilt was the first thing that struck. How things would be managed when I’m not around.”The question is rarely asked of men.“I was so used to being needed,” she admits, “that it stings to realise they can be just fine without me.”Independence here requires mourning. Not failure, but a former version of self-worth tied to indispensability.

‘Too ambitious’, ‘too independent’

Independence, when expressed clearly, often attracts criticism.“Yes,” Arpita says. “Across almost every space I’ve been in.”These labels are warnings. They suggest excess.“What’s called ‘too ambitious’ is usually just a woman being clear about her goals and boundaries,” she says. “Clarity is threatening.”Dr. Sangita has heard another version of the same accusation.“Yes, I’ve often been called selfish,” she says. “Even my husband and daughter consider me self-centred.”But for her, choosing herself is non-negotiable.“I am not physically fit. My life has to function like clockwork,” she explains. “What appears selfish to others is simply self-preservation.”

The body keeps score

The burden of independence is not just emotional. It is physical.“There are days I genuinely feel like giving up,” Arpita says. “Hormonal changes, especially during periods, intensify exhaustion.”The workplace rarely adjusts. And the workday rarely ends at work.“This double shift is so normalised that burnout feels like personal failure rather than systemic neglect.”Dr Medha points out that society often frames this exhaustion strategically.“Calling women tired is a way of calling them unsuited for power,” she says. “It allows old hierarchies to survive while pretending concern.”

Why quitting isn’t simple

Despite fatigue, walking away rarely feels like an option.“Inflation and rising expenses make financial stability non-negotiable,” Arpita says. “But work also gives me purpose.”Independence drains. It also anchors.

Carrying the burden forward

The great burden of independent women is not ambition. It is accumulation. Expectations layered upon responsibilities. Pride braided with guilt. Strength demanded without adequate support.Yet within this weight lies something quietly radical: a refusal to shrink.“I want my child to grow up knowing his mother is a capable woman,” Neha says again, not as a slogan, but as a legacy.Dr. Sangita offers her own message to the next generation.“Independence is a mindset, not a trade-off,” she says. “Protect your boundaries. Respect your partner’s boundaries. That is what makes a relationship last.”Independence, for women, is not a milestone crossed once. It is a continuous act of balancing, resisting, recalibrating.It is not light.But it is chosen.And perhaps the most radical act now is no longer carrying it silently, but finally saying it out loud: this strength has weight, and it deserves to be acknowledged. Go to Source