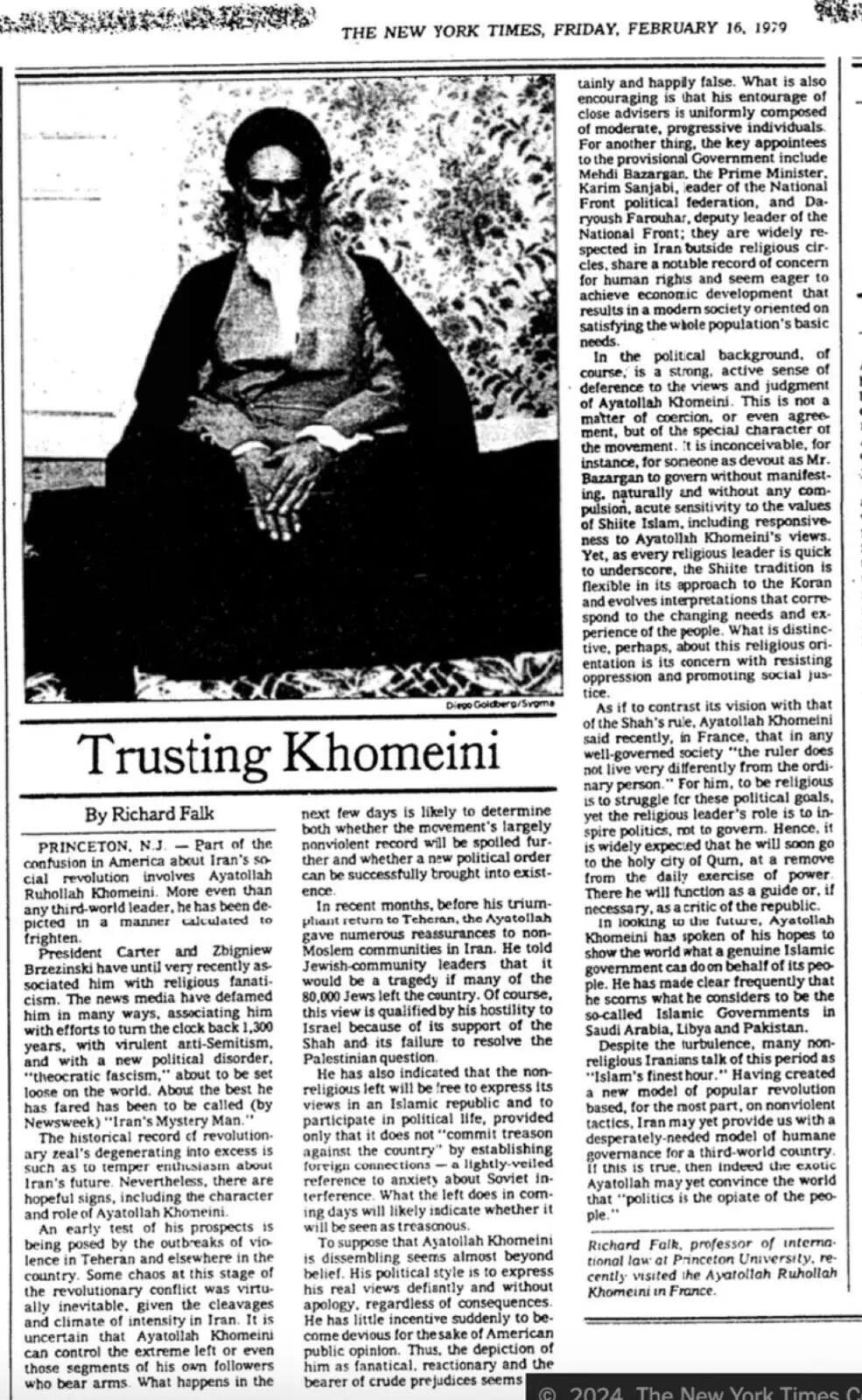

As protests continue to challenge Iran’s clerical establishment, a 1979 opinion article from the New York Times has resurfaced online. Titled Trusting Khomeini, the piece portrayed Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini as a restrained religious figure unlikely to exercise direct political power. Its renewed circulation reflects the sharp contrast between those early interpretations and Iran’s current political reality.

What did the 1979 article argue?

Published days after Khomeini’s return from exile, the article suggested that fears of a theocratic dictatorship were overstated. It argued that Khomeini would act primarily as a moral guide rather than a ruler, that political pluralism would persist, and that his close associates included moderates with records of concern for human rights.

At the time, Iran’s post-revolutionary structure was unsettled. The Shah had fled, institutions were in flux, and many observers believed the broad coalition that overthrew the monarchy would prevent any single faction from monopolising power.

Who wrote it and how did he later reassess it?

The article was written by Richard Falk, then a professor at Princeton University who had met Khomeini shortly before the revolution’s victory. Falk wrote amid widespread Western reassessment of support for the Shah, whose rule was criticised for repression and dependence on US backing. In later reflections, Falk acknowledged that his optimism did not align with how events unfolded. He has said the New York Times headline was not his choice and that the speed with which clerical authority consolidated power was underestimated. In hindsight, he described Khomeini as a revolutionary figure with a rigid, uncompromising vision rather than a symbolic religious guide, conceding that expectations of pluralism proved misplaced.

How did other Western intellectuals view the revolution?

Falk was not alone. One of the most prominent Western thinkers to engage positively with the Iranian Revolution was Michel Foucault, who travelled to Iran in 1978 and wrote a series of essays for European newspapers.Foucault interpreted the uprising as a novel political phenomenon. He described it as a form of “political spirituality”, suggesting it offered an alternative to both Western liberal democracy and Marxist revolution. He believed the movement expressed popular will without aiming to create a clerical state, and he explicitly downplayed the possibility that religious leaders would dominate political life.Events quickly contradicted that assessment. As clerical rule hardened, critics argued that Foucault had underestimated how religious authority could be transformed into a centralised, coercive system of governance. In later years, his writings on Iran became a case study in how intellectual fascination with revolutionary symbolism can obscure the mechanics of power once a revolution succeeds.

What happened after 1979?

Within months, Iran formally became an Islamic Republic. Khomeini assumed the newly created role of Supreme Leader, placing unelected religious authority above elected institutions. Secular, liberal, and left-wing factions that had participated in the revolution were sidelined or eliminated.Over time, the state developed extensive mechanisms to regulate political dissent, social behaviour, and personal freedoms, shaping the political system that exists today.

Why is this debate resurfacing now?

The article’s revival coincides with sustained protests across Iran, many led by women and young people challenging restrictions on dress, speech, and political participation. Protesters have directly questioned the legitimacy of clerical rule and the authority of the Supreme Leader.Against this backdrop, early Western interpretations of the revolution are being revisited as examples of how transitional moments can be misread. The focus is less on assigning blame than on understanding how optimism, ideology, and limited information shaped early judgments.

Why does it still matter?

For Iranians protesting today, the significance of Trusting Khomeini lies not in Western media history but in the long-term consequences of the political order established in 1979. The episode highlights a recurring challenge in political analysis: opposition to an authoritarian regime does not automatically produce a more open or plural system. Seen in that light, the resurfaced article serves as a reminder of how uncertain revolutions can be, and how early assumptions can solidify into realities that last for generations. Go to Source